They meet, and Ralph explains that the goal of his research is to provide an objective, "third-person" account of consciousness. Helen offers a quote from The Wings of the Dove (by Henry James, brother of William -- a nice touch!) to demonstrate that this, indeed, is just what novelists do. Ralph replies that what James does is fiction based on "folk psychology", and that novelists merely "pretend" to know about consciousness.

I suppose that Lodge could just as easily have chosen another James novel, What Maisie Knew (1897), told from the perspective of the titular child, as she tries to make sense of her family's complicated arrangements: divorced parents, and step-parents who are engaged in an affair with each other.

Helen,

for her part, argues that novels actually constitute "thought experiments" in how to represent consciousness. And that without this representation of consciousness, novels wouldn't be novels, and wouldn't be satisfying for anyone to read. (In fact, her description of what a novel would be like without representations of consciousness closely resembles what some cognitive scientists call the "functionalist" approach to behavior -- descriptions that don't stray from "behaviour and appearances", without saying anything about the characters' inner lives.)

Helen's dissertation project was on point of view in

Henry James. In literary studies, "point of view" refers to the way

the story is told -- that is, whose consciousness is being

described. We can identify three different

points of view, or narrative stance, with some

variants. For a fuller discussion,

see The Rhetoric of Fiction by C. Wayne Booth (1961).

If, as Helen claims, fiction wouldn't be satisfying without some representation of the conscious mental states of the characters, narrative stance is related to intersubjectivity.

Intersubjectivity is higher-order intentionality. And perhaps this is the time to remind ourselves of the two quite different meanings of the word "intentionality".

Robin Dunbar

(2000; Kinderman et al., 1998) has calculated that we can keep track

of only about five levels of intentionality. This is consistent with what we

know about the limited capacity of

short-term memory (e.g., George Miller's

"Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two") or the

capacity of working memory (closer to 4 or 5 items).

Interestingly,

there can be more than two levels of intentionality,

even if only two people are involved

-- as illustrated by this New Yorker

cartoon.

I go

through all this because Lisa

Zunshine (2006, 2012), a literature scholar who has

been greatly influenced by

psychology and cognitive science, has argued that

intersubjectivity plays a big role in the English

novel. In fact, she argues that

intersubjectivity in the novel was essentially

invented by Jane Austen, whose novels are full of

narratives in which A believes that B believes

that C believes X.

This is different from the

intentionality in earlier (English)

novels.

For example, there is an

important episode in Persuasion

(1818) in

which Elizabeth and Anne,

encounter Wentworth, to whom

Elizabeth had once been engaged,

but who had been persuaded (hence the title)

to break it off.

Episodes like this proliferate

in Austen's novels

-- much more so than in her 18th-century

predecessors, like Defoe,

Richardson, or Fielding. Interestingly, an article commemorating the 200th

anniversary of Jane Austen's death discussed a

computational analysis of Austen's works by Franco

Moretti, founder of the Stanford Literary Lab and

a proponent of computational criticism, a

branch of digital humanities (DigHum, in

Stanford parlance) which seeks to bring the

techniques of "Big Data" to bear on the analysis

of works of literature ("The Word Choices that

Explain Why Jane Austen Endures" by Kathleen A.

Flynn & John Katz, New York Times Book

Review, 07/16/2017). For example,

Moretti employed principal components analysis to

plot a number of modern English novels, published

between 1710 and 1920, on a pair of axes.

Austen's work was nearly isolated from the others,

for its reference to time markers and states of

mind and avoidance of "muscular" prose.

Another analysis, essentially a word-count, found

that Austen tended to use "intensifying" words

like very, as well as more words referring

to women. And so it went, with its

word-counts and contingency coefficients, leading

to the conclusion, in the words of Flynn and Katz,

that Austen was preoccupied with "states of mind

and feeling, her characters' unceasing efforts to

understand themselves and other people". OK,

but that's a lot of computational firepower to

pick up what Zunshine noted with her naked

eyes, which was Austen's invention of free

indirect narrative and multiple levels of

intentionality. So much for DigHum! |

|

Which is not to say that there aren't

predecessors. As Robin Dunbar

(92004) has noted,

Shakespeare's Othello depends precisely on

multiple levels of intersubjectivity.

|

|

And there are similar episodes in

homer's Odyssey, such as when

Odysseus and his men are held captive by the

cyclops Polyphemus.

Link to a reading of Book IX of Homer's Odyssey (the "Cyclops Episode"). |

|

And, for that matter, there are similar episodes

in the Hebrew Bible:

|

|

|

Or, for that matter, after Adam and Eve tasted the fruit of the Tree of

Knowledge (Genesis 3,

5-12),

|

|

| But of course, intersubjectivity is

essential to the novel, as Helen Reed argues in Thinks....

Zunshine's claim is more interesting:

that higher-order intersubjectivity in the

novel was essentially the invention of Jane

Austen. Zunshine goes on to argue that much modern literature, of the 20th and 21st centuries, is full of multiple levels of intersubjectivity. Zunshine has estimated that Mrs. Dalloway, by Virginia Woolf (1925), involves 6 or 7 levels of intersubjectivity -- far in excess of what Dunbar has estimated most readers can handle. Moreover, Woolf wrote Mrs. Dalloway in what literary scholars call free indirect discourse. She rarely uses quotation marks to indicate dialogue, so that it is difficult to make a distinction between what people think and what they say. No wonder we need CliffsNotes! |

Zunshine's analysis, while innovative, is not completely

unique. Louis Menand, a literature scholar at

Harvard reviewing a number of books about Austen in the New

Yorker ("For Love or Money", 10.05/2020), notes that

"All of Austen's novels are about misinterpretation, about

people reading other people incorrectly. Catherine

Morland, in Northanger Abbey, reads General Tilney

wrong. Elizabeth Bennet reads Mr. Darcy wrong.

Marianne Dashwood, in Sense and Sensibility, gets

Willoughby wrong, and Edmond Bertram, in Mansfield

Park, gets Mary Crawford wrong. Emma gets

everybody wrong."

For a survey of Austen's novels,

prepared on the 250th anniversary of her birth, see "The

Essential Jane Austen" by Sarah Lyall (New

York Times, 07/17/2025).

Perhaps the single most important poem in the English

Romantic tradition, The Prelude is about nothing

less than consciousness -- specifically, Wordsworth's

consciousness. Begun in 1798, and essentially

finished in 1839, the poem went through several different

versions, as befits an autobiographical work, and in fact

received its title by Wordsworth's wife only when it

was published posthumously. As a young man,

Wordsmith had been an enthusiastic supporter of the French

Revolution -- a stance he came to regret during and after

The Terror. In trying to understand how all of this

came to pass, Wordsworth reviews his life in one long epic

poem (14 books!), which was intended to be only a part of

an even longer one, portraying the various episodes in his

life that influenced the shaping and re-shaping of his

mind.

In an extensive analysis of The Prelude,

see by Helen Vendler, reviewing a new edition of the

1805 version of the poem (containing 13 of the 14 books of

the final version), calls the poem "a

unique document of modern consciousness in its constant

mobility -- of times, thoughts, feelings, prospect, and

retrospect" and "a reenactment in real time of the

volatile inner life of a human being".

Vendler further notes that "Wordsworth's momentous -- and

surpassingly expressive -- document belongs in any account

of the evolution of modern secular consciousness in all

its frailty, its tenacity, its bitter self-reproach, its

existential doubt, its exaltation, and its stern

accommodation to the vicissitudes of life" ("'I Heard Voices in My Head'", New

York Review of Books, 02/23/2017).

Woolf also

wrote in a style known stream of consciousness

(also known as interior monologue; they're not exactly the same thing, but

this isn't a course in literary techniques!), which was

essentially the invention of James Joyce (yes, Joyce had

his predecessors, but we've really got to give him

credit). The goal in this style is to

replicate the features of William James's stream of

consciousness, with little or no

punctuation and apparent leaps from one thought or

image to another. In Ulysses,

sometimes the characters' attention is focused

outward, on the sights and sounds they experience

while walking through Dublin; other times, their

attention is focused inward, on their thoughts and

feelings.

The classic example is Joyce's Ulysses

(1922), a novel inspired directly by Homer's Odyssey,

which traces the thoughts and actions of its main

character, Leopold Bloom, as he moves through

Dublin in a single day (June 16, 1904, a date still celebrated in literary quarters as "Bloomsday".

And within Ulysses, the classic

example is Chapter 18 ("Penelope"), which

records the thoughts of Bloom's wife, Molly,

as she goes to sleep at the end of the day.

Link to a reading of Molly Bloom's soliloquy from James Joyce's Ulysses.

A somewhat

different example is found in Joyce's last work, Finnegans

Wake (1939) which, famously begins and ends in the middle of a sentence, and

is littered throughout with puns and

logical leaps. That includes

the title, which lacks the usual apostrophe to

indicate possession: it could refer to "Finnegan's

wake", or funeral; or it could be a pun on "Finn is

again awake". Actually, the traditional

interpretation of this book is that it is an attempt to

represent dream-consciousness -- and, in fact, not just the dreams of a

single dreamer, but rather the dreams of a fairly

large number of dreamers, all intermingled. And

somewhat like a Mobius strip, the first

line picks up where the last line left off, so that the

"dream-process" (if that's what it is) starts up

all over again.

Link

to a reading of the first pages of Finnegans

Wake.

Link to an annotated online text of James Joyce's Finnegans Wake.

As for Woolf herself, Michael Cunningham

(whose novel, The Hours, later turned into an

excellent film by , is based on Mrs. Dalloway

wrote an appreciation in the New York Times Book

Review ("Michel Cunningham on Virginia Woolf's

Literary Revolution", 12/27/2020):

In “Mrs. Dalloway” we follow Clarissa, a society hostess, well-heeled and gracious, a little false, no longer young, as she walks through London on a balmy day in June....

In “Mrs. Dalloway”’s London, consciousness passes from one character to another in more or less the way a baton is passed among members of a relay race. If, for instance, a young Scottish woman, newly arrived in London, wanders lost and disconsolate through Regent’s Park, we briefly enter her mind, feel her unhappiness (“the stone basins, the prim flowers … all seemed, after Edinburgh, so queer. … She had left her people; they had warned her what would happen”) until she is noticed by an older woman, at which moment we switch to the consciousness of the old woman, who, envying the first woman’s youth, mourns the loss of her own (“it’s been a hard life. … What hadn’t she given to it? Roses; figure; her feet too.”) until we are snapped back to Clarissa, as she returns home to learn she has not been invited to an exclusive, politically inspired luncheon.

Maybe the book’s most singular innovation, however, is the alternating stories of Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Warren Smith, who do not know of each other’s existence until the very end, when Septimus arrives at Clarissa’s party as a true ghost, not only disembodied but nameless, nothing left of him but his suffering and his violent end. At the very last moment, their lives converge, but only across the divide of mortality itself.

While Septimus is still alive, though, we move back and forth between the utter veracity of Clarissa’s domain, which can run to the banal, and the tumultuous delusions of Septimus’s, where a little banality might be a welcome relief.

On this side of the

Atlantic, William Faulkner employed

the stream-of-consciousnes technique in

The Sound and the Fury (1929).

Tracing the decline of a Mississippi family, the Compsons,the story is told mostly

through the voice of Benjy, the

youngest son, who is either brain-damaged

or mentally retarded, and whose

perceptions and memories come out in a disorganized flow

-- to which other family members also contribute, so that we get constantly shifting perspectives and locations in

space and time. In a letter to Malcolm Cowley,

Faulkner wrote that "I'm trying to say it all in one

sentence, between one Cap and one period. I'm

still trying to put it all, if possible, on one

pinhead.

Of course, neither

Joyce nor Faulkner invented the interior

monologue. Soliloquies,

in which a character speaks his thoughts out loud, go back at least as far as

Shakespeare's Hamlet ("To

be or not to be, that is the question...")

and Macbeth ("Tomorrow,

and to-morrow, and to-morrow/Creeps

in this petty pace from day to day,/To the

last syllable of recorded time...).

Soliloquies are different

from monologues, in which the actor is

really speaking to another

character, or to the audience. In

the soliloquy, the character

is speaking to him- or herself.

In the 20th century, the

soliloquy was

developed further by Eugene O'Neil's Strange

Interlude (1923; also a 1932 movie starring Normal

Shearer and Clark Gable, and a 1988 television

adaptation starring Glenda Jackson and David

Dukes). In this play, the actors will occasionally

step out of the action and speak

their thoughts out loud to the

audience -- thoughts that may be quite different

from those conveyed by the

dialogue or action. In the film version, the soliloquies were

done as voiceovers. As of 2016, Strange

Interlude had not been

released on video, but you can watch

it on YouTube.

The play won the Pulitzer Prize

for Drama in 1928, the year it

was first produced.

In the 20th century, the

soliloquy was

developed further by Eugene O'Neil's Strange

Interlude (1923; also a 1932 movie starring Normal

Shearer and Clark Gable, and a 1988 television

adaptation starring Glenda Jackson and David

Dukes). In this play, the actors will occasionally

step out of the action and speak

their thoughts out loud to the

audience -- thoughts that may be quite different

from those conveyed by the

dialogue or action. In the film version, the soliloquies were

done as voiceovers. As of 2016, Strange

Interlude had not been

released on video, but you can watch

it on YouTube.

The play won the Pulitzer Prize

for Drama in 1928, the year it

was first produced.

Going Joyce and Faulkner one

better, in 2019 Lucy Ellman published Duck,

Newburyport, a novel consisting, mostly, of

a single sentence of more than 426,000 words

spread out over more than 1000 pages. Parul

Seghal, reviewing the book in the New York

Times ("A Thousand-Page Novel -- Made Up of

Mostly One Sentence -- Captures How We Think Now",

09/04/2019), noted that the form of the book

"mimics the way our minds move now: toggling

between tabs, between the needs of small children

and aging parents, between news of ecological

collapse and school shootings while somehow

remembering to pay taxes and fold the

laundry". "In just a few lines, the narrator

[an Ohio mother of four] can hurtle from toilet

training her son to Howard Hughes, her weak ankles

to white supremacy." Seghal concludes that

"The capaciousness of the book allows Ellmann to

stretch and tell the story of one family on a

canvas that stretches back to the bloody days of

Western expansion, but its real value feels deeper

-- it demands the very attentiveness, the care,

that it enshrines.

Going Joyce and Faulkner one

better, in 2019 Lucy Ellman published Duck,

Newburyport, a novel consisting, mostly, of

a single sentence of more than 426,000 words

spread out over more than 1000 pages. Parul

Seghal, reviewing the book in the New York

Times ("A Thousand-Page Novel -- Made Up of

Mostly One Sentence -- Captures How We Think Now",

09/04/2019), noted that the form of the book

"mimics the way our minds move now: toggling

between tabs, between the needs of small children

and aging parents, between news of ecological

collapse and school shootings while somehow

remembering to pay taxes and fold the

laundry". "In just a few lines, the narrator

[an Ohio mother of four] can hurtle from toilet

training her son to Howard Hughes, her weak ankles

to white supremacy." Seghal concludes that

"The capaciousness of the book allows Ellmann to

stretch and tell the story of one family on a

canvas that stretches back to the bloody days of

Western expansion, but its real value feels deeper

-- it demands the very attentiveness, the care,

that it enshrines.

Another

literary exploration of consciousness is to

found throughout Marcel Proust's massive,

seven-volume, 1925 novel, Remembrance

of Things Past (that's the title of the

original English translation, and still my

preference; the new translation is

entitled In Search of Lost Time).

The series is an extended

meditation on involuntary memory, when some

object or event unexpectedly stirs up a memory. The classic

example, from Swann's Way, the

first volume, is the "madeleine episode",

in which the first taste of a cookie dipped in

tea brings back a rush of

memory of the protagonist's childhood.

Jonah Lehrer, a prominent popular-science writer, wrote a book titled Proust was a Neuroscientist (2007), in which he argued that many modern scientific discoveries about the mind and brain were anticipated by Proust and other literary, musical, and artistic figures. But Proust wasn't any kind of neuroscientist, or even a psychologist. That's Lodge's point in Thinks...: that you don't have to be any kind of scientist to have interesting, valid things to say about consciousness.

Edward Rothstein, reviewing

"Marcel

Proust and Swann's Way: 100th

Anniversary" an exhibit at the Morgan

Library in New York City, comments

on Proust's depiction of conscious

recollection ("Proust,

for Those with a

Memory", New York Times,

02/15/2013).

"Perhaps I am as thick as two short planks," reads one [prepublication review], "but I cannot understand how a man can take 30 pages to describe how he turns round in his bed before he finally falls asleep."

But anyone who reads that first volume of A la Recherche du Temps Perdu, translated as Remembrance of Things Past, has no problem understanding how 30 pages might be required to capture the turnings of self-consciousness and their cascades of recollection.

Somewhat

ironically, Rothstein notes that the

exhibit makes clear that the "Madeleine Episode" didn't

start out thta way. In a draft

from 1909, the narrator dips toast

in his tea; in a 1910 version, he dips biscottes.

So much for the reliability of

memory!

For more,

see "Cognitive

Realism and Memory in Proust's Madeleine Episode" by Emily

Troscianko, Memory Studies,

2013.

The

structure of Thinks... reflects some of these

literary trends. First, the

book alternates among three different points of view:

Ralph (speaking into his tape-recorder), Helen (writing

in her diary), and an omniscient narrator. It

strikes me that Ralph's exterior monologues

(exterior because they're spoken into a recorder) are

something of a parody

of Molly Bloom's soliloquy in Ulysses.

There are some breaks in this plan.

Tom

Stoppard, the English playwright famous for exploring philosophical and social commentary

topics in his work: Every Good Boy

Deserves Favour (1977)

was inspired by the Gulag archipelago, while Arcadia (1993) dealt with

chaos theory, among other things (including landscape

architecture). The Hard Problem (2015) takes its title from David Chalmers's analysis of the mind-body-problem: Why do we have subjective

experience, and how does subjective experience

happen? I saw

its West Coast Premiere at

the American Conservatory Theatre, in San

Francisco, in 2016, where the stage set

reminded me a little of the architecture of

the Salk Institute in La Jolla, a famous

center for the study of the mind-body

problem (if that was intentional, then

someone was doing their homework).

Tom

Stoppard, the English playwright famous for exploring philosophical and social commentary

topics in his work: Every Good Boy

Deserves Favour (1977)

was inspired by the Gulag archipelago, while Arcadia (1993) dealt with

chaos theory, among other things (including landscape

architecture). The Hard Problem (2015) takes its title from David Chalmers's analysis of the mind-body-problem: Why do we have subjective

experience, and how does subjective experience

happen? I saw

its West Coast Premiere at

the American Conservatory Theatre, in San

Francisco, in 2016, where the stage set

reminded me a little of the architecture of

the Salk Institute in La Jolla, a famous

center for the study of the mind-body

problem (if that was intentional, then

someone was doing their homework).

But

the play also deals with the Prisoner's

Dilemma (in fact, it begins with a scene in

which two main characters, Spike and Hillary,

try to solve the problem), altruism vs.

egotism, and -- wait for it -- the Financial

Crisis of 2007-2009. Hillary is an

English university student seeking a

post-graduate fellowship at the Krohl Insitute

for Brain Science. While waiting for her

appointment, she learns from Amal, another applicant,

that the head of the Institute is mostly

interested in "The Hard Problem"; Hillary,

at first, doesn't even know what that is. Once

she finds out, she discusses the

problem with Spike, a die-hard

materialist, insisting (alluding to

Morton Prince and others) that there

is a difference between mind and

body, and there must be some "mind

stuff that doesn't show up in a

scan" (as I say, Stoppard does his

homework). But like most

everyone else, Hillary finds The

Hard Problem unsolvable: "Every

theory proposed for the problem of

consciousness has the same degree of

demonstrability as divine

intervention".

Amal, for his part, proposes to study Libet's "unconscious readiness potential" while people are solving the PD. Amal eventually abandons brain science for high finance, and gets caught up in the Financial Crisis. I won't tell you what happens to Hillary (or Spike) -- except to say that I found the ending to be a completely unconvincing and unnecessary coincidence.

I will tell you, though, that Stoppard

doesn't stick with The Hard Problem

very long.

The play, while entertaining, is sort of a

mishmash: it's telling that, in the ACT playbook,

Stoppard tells us that he

originally intended to write a play about

the Financial Crisis. The Guardian,

reviewing the English production

(02/01/2015),

criticized Stoppard for seeming to promise, but

not delivering, a serious exposition of and

commentary on The Hard Problem. Vinson Cunningham made a similar complaint,

reviewing the New York revival of The Hard Problem

in the New Yorker (12/10/2018). Reviewing the ACT

production, the San Francisco

Chronicle called the play "a string of

nonevents". Somehow, consciousness

slipped in, but the play is really more

about morality and altruism -- which is probably why it begins with

the PD. But maybe that's

Stoppard's point: for all the attention to

the mind-body problem, maybe the real

hard problem is how to behave morally in a materialist universe.

For my money, Lodge did a much better job of dealing with these issues, and with putting them into literature.

Representations of conscious mental states may lie at the heart of the novel (and other forms of fiction), but other art forms have also gotten in on the game.

The most

obvious of these is Impressionism, which got its

start in France in the mid-19th century. Prior to

this time, at least from the Renaissance onward, up

through the Realism of Daumier, Courbet, David, and

others, paintings were supposed to be

realistic representations of people or scenes from

history, the Bible, or mythology

-- as the viewer were looking

through a window out onto a scene.

For a nice article on Monet's "water lilies" paintings, see "Lasting Impressions" by Jackie Wullschlager, Smithsonian, 09-10/2024. It's drawn from her book, Monet: The Restless Vision (2024). A whole bunch of these waterlily paintings were installed, under Monet's supervision, at the Musee de l'Orangerie in Paris. If you get to Paris, don't miss them.

In

some respects this trend

continued with a movement known as post-impressionism.

The post-impressionists maintained the

impressionists' emphasis on momentary

perception, but they attempted to give their

art a more deliberate, finished look.

An excellent example is "A Sunday

afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte",

by Georges Seuat (1886),

the jewel in the crown of the collection at

the Art Institute of Chicago

(if you ever get to Chicago, don't miss

it!). Seurat himself was greatly influenced by the

psychological theory of color

perception dominant

at the time, proposed by Thomas Young and

Hermann von Helmholtz, who

showed that any

color could be produced by an

appropriate mixture of just three "primary" colors -- red, green,

and blue; this suggested that

we have receptors in the eye

tuned to short,

long, and medium wavelengths

of light (we now

know that this theory isn't

quite right, but that makes

no difference to the story).

In

making his painting (and many others

afterwards), Seurat applied pure color in

tiny drops (a technique known as pointillism)

-- and just to make it clear what he was

doing, he painted a frame around the

picture consisting solely of those same

dots of paint. Previous painters

mixed their paints before applying them to

the canvas. But Seurat understood

that, to paraphrase, color is mixed in

the eye, not on the palette.

A related movement,

which arose in Northern Europe

and the Nordic countries, was Expressionism,

which had the goal of depicting the artists internal emotional,

rather than perceptual, state. .

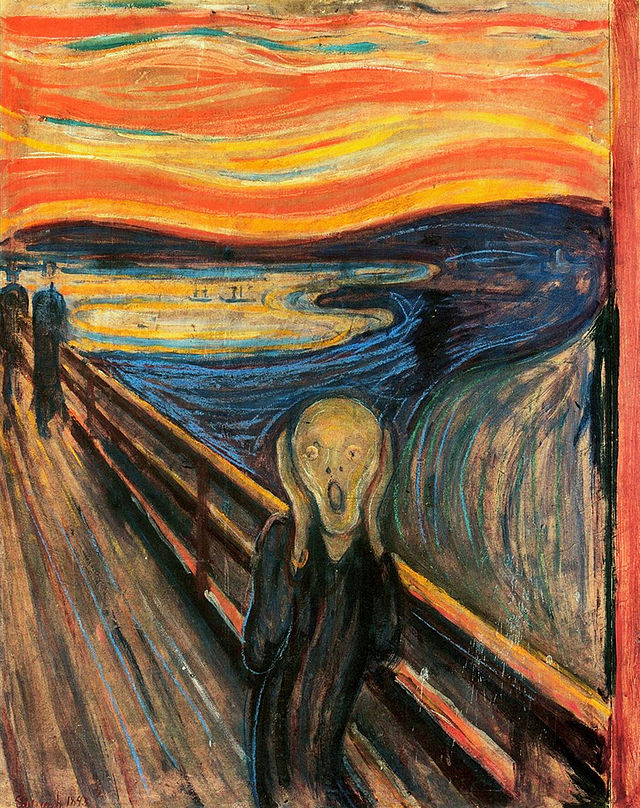

The classic example, and by many accounts the painting

that got the whole movement going, was "The Scream",

several versions of which were painted by Edvard Munch

from 1893-1910 (this one hangs in the

National Gallery, Oslo, Norway). Other

expressionists were the artistic groups known as Die Brucke ("The Bridge"), led by Ernst

Kirchner; and Die Blaue Reiter ("The Blue

Rider"), inspired by a 1903 painting by Wassily Kandinsky.

A related movement,

which arose in Northern Europe

and the Nordic countries, was Expressionism,

which had the goal of depicting the artists internal emotional,

rather than perceptual, state. .

The classic example, and by many accounts the painting

that got the whole movement going, was "The Scream",

several versions of which were painted by Edvard Munch

from 1893-1910 (this one hangs in the

National Gallery, Oslo, Norway). Other

expressionists were the artistic groups known as Die Brucke ("The Bridge"), led by Ernst

Kirchner; and Die Blaue Reiter ("The Blue

Rider"), inspired by a 1903 painting by Wassily Kandinsky.The Expressionists were influenced by Benedetto

Croce, an Italian philosopher of aesthetics who argued

that art reflected an intuitive synthesis of image and

feeling. Artists are not representing reality:

they are representing emotion. They were also

influenced by the emerging theories of Sigmond Freud,

whose treatise on The Interpretation of Dreams,

published in 1899, became an international

best-seller. To make a long story short, argued

that dream imagery, was the product of unconscious

affects and drives.

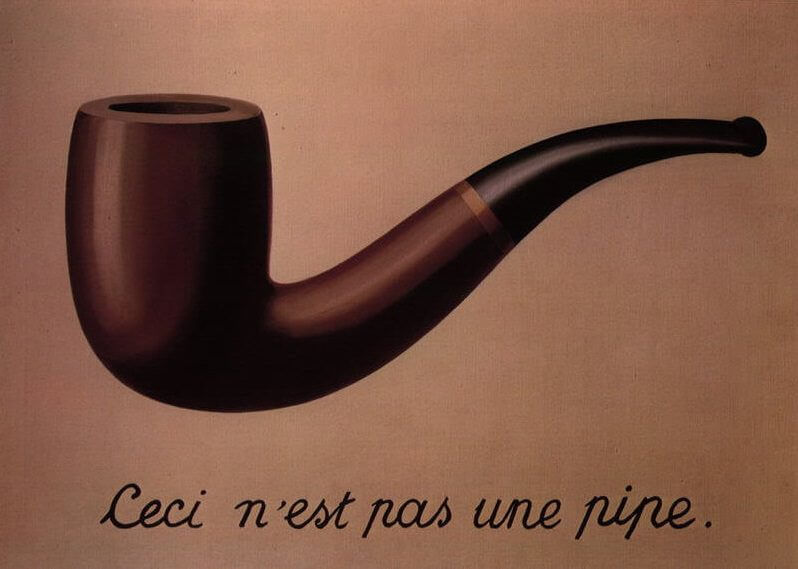

Freud, and especially his dream theory, was an even

greater influence on another artistic movement, known

as surrealism. The surrealists, led by

Salvatore Dali and Henri Magritte, rejected the notion

of art as any kind of representation of the external

world (that it was just such a representation was an

assumption shared by both the Impressionists and the

Realists). Instead, they asserted that art

should represent the internal world, the world

of the mind, and especially that of the unconscious

mind. (The surrealists were also influenced by

C.G. Jung's theory of the collective unconscious.)

Reviewing a number of books and exhibits celebrating

the 100th anniversary of the Surrealist movement in

the arts and literature, Jackson Arn

The exalted subconscious, the spurning of reason—these are the precepts of Breton’s manifesto, familiar from any art-history textbook. What the textbooks rarely report is that he begins by dunking on Dostoyevsky—specifically, a short description of a room from “Crime and Punishment.” The room is small, and outfitted with yellowish furniture, yellow wallpaper, muslin curtains, and geraniums in the windows. That’s it, more or less; the writing isn’t great, but far from terrible. To Breton, however, this passage demonstrates what’s so wretched about realism in art: it dares to wallow in everyday reality, the stuff that he calls “the empty moments of my life.” All avant-gardes need a devil. Surrealism, via faith in the id’s boundless originality, was meant to save our souls from endless stacks of “school-boy description,” so clichéd that Dostoyevsky could have taken them from “some stock catalogue” ("The Bad Dream of Surrealism", New Yorker, 08/12/2024).

The year 2024 is the 100th anniversary of Andre Breton's famous first Surrealist Manifesto, issued on October 15, 1924. Yves Goll, another early Surrealist, had issued his own surrealist manifesto on October 1 of that year, but it's Breton's that made it into all the art-history books. Breton issued a second manifesto in 1929, but it's the first one, from 1924, that really counts. For a review of a host of books and exhibitions celebrating the centenary of Surrealism, see "A Century of Surrealism" by Jed Perl, New York Review of Books, 05/15/2025.

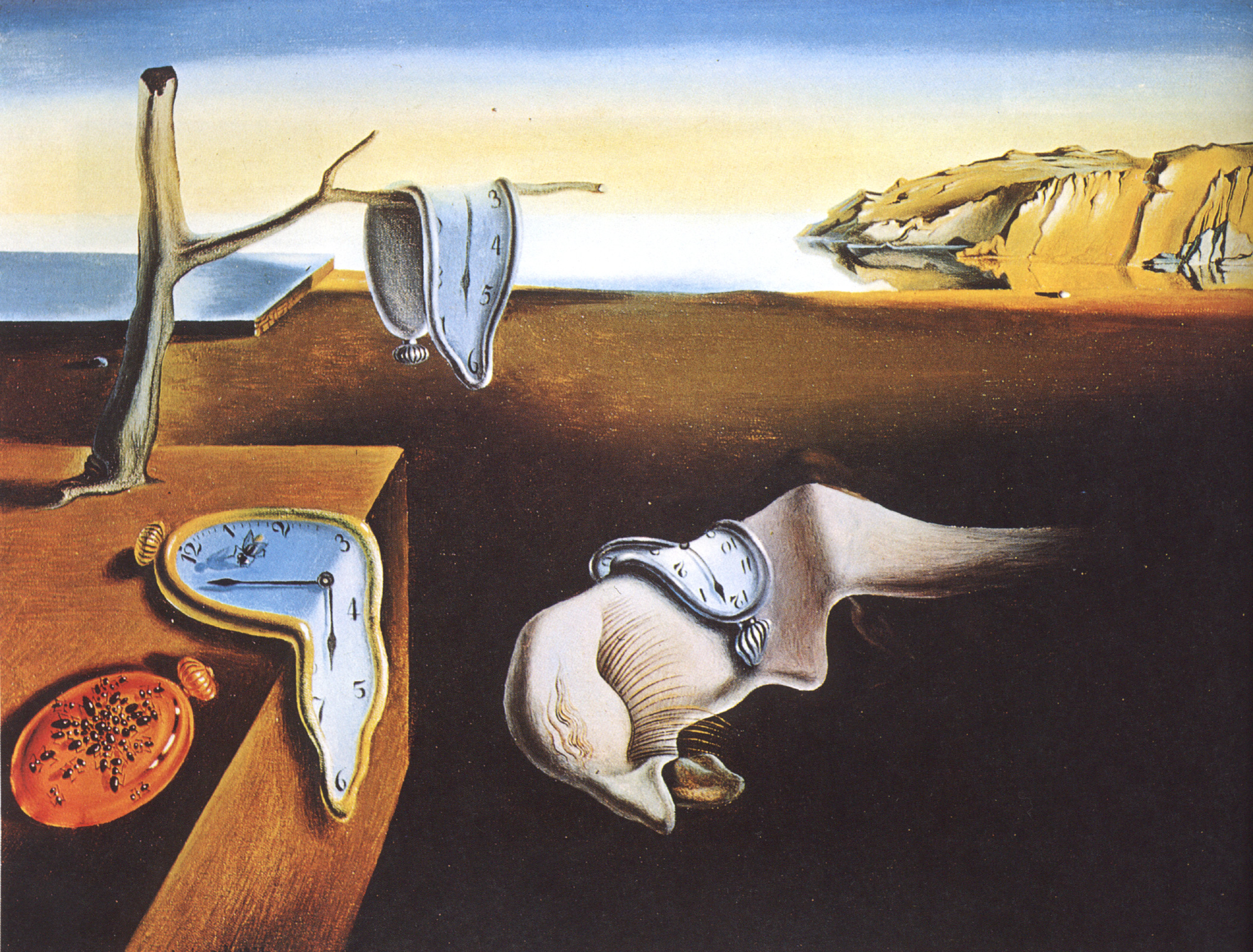

The

surrealist ethos is perhaps best represented by Dali's The

Persistence of Memory (1931), with its melted

watches symbolizing the suspension of time, and the

inconsistent lighting and shadowing symbolizing the

suspension of rationality. This is not an image of

something that could exist in the real world outside the

mind.

The

surrealist ethos is perhaps best represented by Dali's The

Persistence of Memory (1931), with its melted

watches symbolizing the suspension of time, and the

inconsistent lighting and shadowing symbolizing the

suspension of rationality. This is not an image of

something that could exist in the real world outside the

mind.

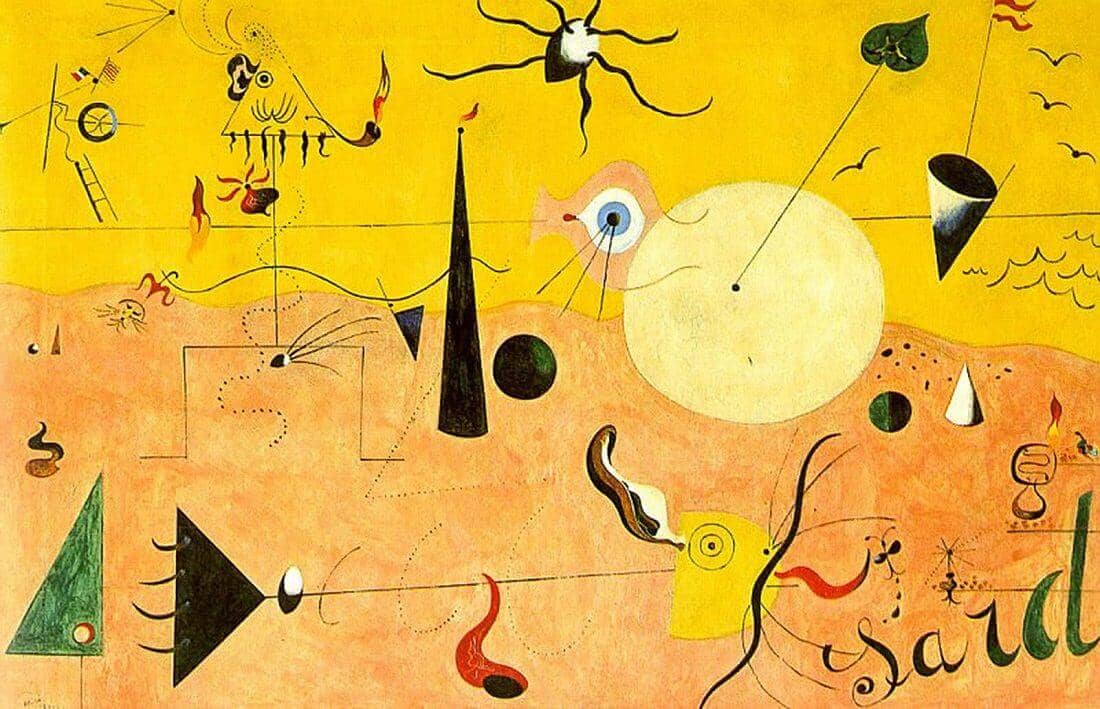

A variant on surrealism was surrealist automatism

-- an artistic technique inspired by automatic

writing, the Ouija Board, and other "mediumistic"

methods -- and, of course, William James's own

description of the stream of consciousness.

In automatic drawing, the artist allowed his

or hand to move, apparently randomly,

around the canvas or paper, so

that the resulting image reflected

the operation of unconscious processes.

Doodling is an excellent

example of automatic drawing. Joan Miro, a Spanish

Surrealist, often incorporated into his painting

repetitive shapes and lines that appeared in his doodles

-- as in Catalan Landscape (1923-1924).

Doodling is an excellent

example of automatic drawing. Joan Miro, a Spanish

Surrealist, often incorporated into his painting

repetitive shapes and lines that appeared in his doodles

-- as in Catalan Landscape (1923-1924).

OBJECTS

A CARAFE, THAT IS A BLIND GLASS.

A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing. All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.

GLAZED GLITTER.

Nickel, what is nickel, it is originally rid of a cover.

The change in that is that red weakens an hour. The change has come. There is no search. But there is, there is that hope and that interpretation and sometime, surely any is unwelcome, sometime there is breath and there will be a sinecure and charming very charming is that clean and cleansing. Certainly glittering is handsome and convincing.

There is no gratitude in mercy and in medicine. There can be breakages in Japanese. That is no programme. That is no color chosen. It was chosen yesterday, that showed spitting and perhaps washing and polishing. It certainly showed no obligation and perhaps if borrowing is not natural there is some use in giving.

A SUBSTANCE IN A CUSHION.

The change of color is likely and a difference a very little difference is prepared. Sugar is not a vegetable.

Callous is something that hardening leaves behind what will be soft if there is a genuine interest in there being present as many girls as men. Does this change. It shows that dirt is clean when there is a volume.

A cushion has that cover. Supposing you do not like to change, supposing it is very clean that there is no change in appearance, supposing that there is regularity and a costume is that any the worse than an oyster and an exchange. Come to season that is there any extreme use in feather and cotton. Is there not much more joy in a table and more chairs and very likely roundness and a place to put them.

A circle of fine card board and a chance to see a tassel.

What is the use of a violent kind of delightfulness if there is no pleasure in not getting tired of it. The question does not come before there is a quotation. In any kind of place there is a top to covering and it is a pleasure at any rate there is some venturing in refusing to believe nonsense. It shows what use there is in a whole piece if one uses it and it is extreme and very likely the little things could be dearer but in any case there is a bargain and if there is the best thing to do is to take it away and wear it and then be reckless be reckless and resolved on returning gratitude.

Light blue and the same red with purple makes a change. It shows that there is no mistake. Any pink shows that and very likely it is reasonable. Very likely there should not be a finer fancy present. Some increase means a calamity and this is the best preparation for three and more being together. A little calm is so ordinary and in any case there is sweetness and some of that.

A seal and matches and a swan and ivy and a suit.

A closet, a closet does not connect under the bed. The band if it is white and black, the band has a green string. A sight a whole sight and a little groan grinding makes a trimming such a sweet singing trimming and a red thing not a round thing but a white thing, a red thing and a white thing.

The disgrace is not in carelessness nor even in sewing it comes out out of the way.

What is the sash like. The sash is not like anything mustard it is not like a same thing that has stripes, it is not even more hurt than that, it has a little top.

A BOX.

Out of kindness comes redness and out of rudeness comes rapid same question, out of an eye comes research, out of selection comes painful cattle. So then the order is that a white way of being round is something suggesting a pin and is it disappointing, it is not, it is so rudimentary to be analysed and see a fine substance strangely, it is so earnest to have a green point not to red but to point again.

A PIECE OF COFFEE.

More of double.

A place in no new table.

For a survey of the role of dreams in 20th-century art, see Dreams 1900-2000: Science, Art, and the Unconscious Mind, edited by Lynn Gamwell. The "science" is mostly psychoanalysis, so you have to take it with a grain of salt. But even if the science is bogus, there's no question that the psychoanalytic theory of dreams was a great influence on 20th-century art. The book includes "The Psychology and Physiology of Dreaming: A New Synthesis"an essay by Ernest Hartmann, a psychoanalyst who was also a leading dream researcher.

No presentation on

consciousness in art would be complete without

at least a mention of psychedelic art, a

movement which arose in the 1960s (of course!)

to depict, and sometimes enhance, the experience

of those who took

psychedelic drugs such as LSD.

Psychedelic art used bright, contrasting

colors, often arranged in kaleidoscopic patterns. Psychedelic artists were also attracted to paisley patterns, and fractals.

No presentation on

consciousness in art would be complete without

at least a mention of psychedelic art, a

movement which arose in the 1960s (of course!)

to depict, and sometimes enhance, the experience

of those who took

psychedelic drugs such as LSD.

Psychedelic art used bright, contrasting

colors, often arranged in kaleidoscopic patterns. Psychedelic artists were also attracted to paisley patterns, and fractals.

This page last revised 07/26/2025.