Absorption, daydreaming, and absent-mindedness occur more or less spontaneously -- though of course, people can deliberately engage in both sorts of activities. The alterations in consciousness associated with meditation, however, require deliberate, conscious effort, training, and discipline.

At first pass, we can identify

two great meditative traditions, both associated with South

and East Asia:

Interestingly, although -- as we shall see later -- neuroscientists have become involved in studying what happens in the brain during meditation, both the Vedic-Hindu and Buddhist traditions hold that consciousness exists independently of the brain. For an excellent account of the relations between the Eastern meditative traditions and contemporary neuroscience, see Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self-and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy by Evan Thompson (2014). Thompson himself doubts that consciousness can exist independent of the brain, either in mediation or in states like the out-of-body or near-death experience, discussed in the earlier lectures on Mind Without Body. Rather, he argues that OBEs and NDEs are experiential states correlated with particular brain states -- specifically states of the brain in the process of dying. But I digress.

Yoga

and Zen were introduced to America at the World Parliament

of Religions, held in conjunction with the World's Columbian Exposition, a World's Fair held in Chicago in 1893.

The Parliament brought together leading authorities of

most of the world's religions, who

gave lectures and demonstrations of their beliefs and

practices. Among the most memorable of these was

Swami Vivekananda,

a prominent yogi from India, and Soen Shaku, a

Buddhist monk who led the Japanese delegation.

Thereafter, both yoga and zen were gradually absorbed

into American culture -- in the

process of which they gradually became secularized, dissociated from

their religious and philosophical origins, and

commodified, taught for a fee.

The music historian Orlando Figgis, writes of Rachmaninoff's All-Night Vigil (combining the Matins and Vespers), "As in Russian folk song, too, there is a constant repetition of melody, which over several hours -- the Russian Orthodox service can be interminably long -- can have the effect of inducing a trance-like state of religious ecstasy" (quoted by Paul Hillier in an essay in The Steve Reich Reader).

Western meditative traditions have been much less popular topics of study -- which may bespeak a tendency toward exoticism, or what Edward Said called "Orientalism", among Westerners.

The via negativa is perhaps

represented by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a Syrian monk

whose books (e.g., The Celestial Hierarchies and The

Divine Names, written in Greek and collectively known as

the Corpus Areopagiticum or the Corpus Dionysiacum)

appeared in the 5th or 6th century CE. Pseudo-Dionysius

argued that people must clear their minds of any knowledge of,

or interest in, the material world in order to know God.

Most Catholic mystics, however, including St. Augustine,

represent the more positive approach: through the

material world, not in opposition to it.

Clark cites as an example St. Francis of

Assisi. Whereas earlier Catholic mystics, like Bernard of

Clairvaux, mostly wrote for literate clergy who could read

Latin, Francis sought to convey the mystical experience of union

with God to lay people through nature (after all, he even

preached to the birds!). There were also several female

mystics, the most famous of whom was probably Hildegard of

Bingen, who was also a composer whose music is heard in churches

and concerts to this day. Also Meister Eckhart , Thomas a

Kempis, and St. Catherine of Siena -- one of only three female

"Doctors of the Church". .

At age thirty, Julian experienced sixteen extended and agonizing visions of God, which she collected in a book called "Revelations of Divine Love". She describes feeling "a supreme spiritual pleasure in my soul" and being "filled with eternal certainty," a feeling "so joyful in me and so full of goodness that I felt completely peaceful, easy and at rest, as though there were nothing on earth that could hurt me". But, she writes, "this only lasted for a while, and then my feeling was reversed and I was left oppressed, weary of myself, and so disgusted with my life that I could hardly bear to live"Well, maybe Ecstasy is the path to God and maybe not. But what strikes me as more interesting is the aftermath of Julian's experiences. She didn't just come back down to earth, as it were. Instead, her emotional state went below zero, to something like its hedonic opposite: joy was replaced by disgust. This is exactly what we would predict from what is known as the opponent-process theory of acquired motivation, which I discuss at length in my introductory course. Briefly, the opponent-process theory postulates that every affective state (call if the "A State") invokes its hedonic opposite (call it the "B State") as a sort of slave state. When the stimulus that elicited the A State disappears, the B state comes rushing in with a vengeance. These temporal dynamics of affect predict the "high", tolerance, and withdrawal associated with drug addiction -- and further suggest that addiction itself is motivated more by the desire to avoid the agonies of withdrawal than by the desire to obtain the pleasures of the high. Be that as it may, one wonders if the opponent-process theory applies to mystical experiences as well: if they are followed by crashes rather than a simple return to baseline; and whether something like tolerance occurs as a result of their repetition.

This kind of delirious experience is seemingly a human constant, recounted with more or less identical phrasing in many different eras and attributed to many different sources. In 1969, the British biologist Alister Hardy began to compile a database of thousands of narratives that sound almost exactly like Julian's.... Technically, Hardy's archive is a compendium of religious experiences, but the accounts within it resemble transcripts from the supervised drug sessions that were conducted in the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties, during the brief period when Ecstasy could be used in therapeutic settings.

The unitive mysticism of Pseudo-Dionysius (aka "Dennis" or "Denys"; 5th-6th c. CE), as represented in his Mystical Theology derived from Plotinus (d. 270 CE), a pagan "neo-Platonist" philosopher (in his Lecture on "Plotinus and Neo-Platonism" Cary calls him the "last great philosopher of pagan antiquity). Recall Plato's "Allegory of the Cave": it is as if we are chained facing the wall of a cave, and all we can see are the shadows cast by reality -- the Forms -- by a fire. The philosopher is like a prisoner freed from the cave, who can see reality directly. For Plotinus, this is the "moment of understanding" when the human mind connects with the "divine Mind". For most of us, if we even get that far, this connection occurs only momentarily. But for some, the ability to see reality directly is a permanent state of cognitive existence. And that's not all. Beyond (really, above) the Forms and the divine Mind is "the One". If we're really lucky, we can get beyond the duality of seer (the one who knows the Forms) and seen (the Forms themselves), and achieve union with the One.

Just as St. Thomas Aquinas based his theology on Aristotle, so Pseudo-Dionysius based his on Plotinus, and Plato. We don't need to go into the details here, except to state the obvious: Plotinus' "the One" is P-D's God. God is the "incomprehensible One" who "passeth all understanding". It's not possible to understand God, but it is possible to achieve an ecstatic union with God when the soul goes outside and beyond itself, and "passes over" into God.

The Dionysian tradition of Christian mysticism comes to a head, at least for Cary, in the identity mysticism of Meister Eckhart (c. 1260-c.1327), another Christian neo-Platonist, who taught that the highest part of the individual soul is eternally identical with the divine One, or God. Just as Jesus Christ was "eternally begotten of the Father", even before the Incarnation, so this eternal begetting occurs in each of our individual souls. Put another way, God is already present in each individual person's soul, and the whole point of contemplation was to discover God in our own souls. In the 14th century, this idea was considered heretical, because orthodox Christian theology enforced a fundamental distinction between the soul and God. And, indeed, Eckhart was tried for heresy, and recanted all that was "wrong" in his teachings (without, apparently, specifying what those errors were).

Since Eckhart's time, most

Christian mystics have sought the union of the soul

with God, rather than discovering the identity of

the soul with God, thus preserving the basic distinction

between uncreated Creator and created creature. But

the basic idea, rooted in Pseudo-Dionysius and Meister

Eckhart, of achieving ecstatic union with God through

contemplative activity that transcends both the senses and

the intellect, can still be seen in the classics of the

Christian meditative tradition:

One exception has been recent work on Christian evangelicals by Tanya Luhrmann, an anthropologist, as summarized in her book, When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God (2012).

Modern evangelicalism is a very varied religious movement with its roots in the First and Second Great Awakenings, revivals of religious belief and practice that occurred in the late 18th and mid 19th centuries (Luhrmann identifies the 1960s as a "Third Great Awakening"). Evangelicals typically hold fundamentalist religious beliefs, such as the inerrancy of the Bible as God's true word. But in the present context, what is interesting about evangelicals is what Luhrmann calls their "concrete experience of God's nearness". Evangelicals may or may not speak in tongues -- glossolalia, which in and of itself may represent an alteration in consciousness), but they typically seek a direct experience of the presence of God.

Luhrmann (2012) studied a particular Evangelical church known as the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, whose members engage in a disciplined form of prayer, acquired through training -- much like a yoga or Zen master -- in which they not only talk to God, but God talks back, to them, personally. Her work employed the method of participant observation, in which she herself participated in the church's activities (church members knew what she was doing, so there was nothing dishonest about this).

From a materialist perspective, of course, this

is all a product of imagination. But, Luhrmann argues, it is

imagination of a very special sort, in which the person comes

"to treat the what the mind imagines as more real than the world

one knows". Everyone has the capacity for this kind of absorption,

to at least some degree (Luhrmann cites Tellegen's work in this

respect), but Luhrmann argues that members of the Vineyard, as

well as other like-minded and like-practiced evangelicals, have

honed absorption into a cognitive skill that is put to the

purpose of their religion.

Based on her observations, and reading in the

Christian mystical tradition, Luhrmann has classified Christian

prayer into three main categories.

For reasons that only a sociologist of science could explain, however, this Western, Christian mystical tradition has not been the focus of scientific study (Luhrman is the exception, and her work is well worth getting to know). All the science has been focused on yoga, and Zen, and more recently Tibetan Buddhism. So that's where we turn for the rest of these lectures.

|

| "Three Aspects of the Absolute", from a manuscript of the Nath Charit painted by Bukali (1823). The left panel represents the origin of existence; the center and right panels, its "emanations" into consciousness and form, represented by a Nath yogi. From Yoga: The Art of Transformation (see below). Note the resemblance to "The Emergence of Spirit and Matter", the image at the top of the lecture supplements on Mind and Body. |

Yoga meditation has its roots in the Yoga

Sutras by Patanjali, written about 200 BCE. The Samkhya

school of Hinuism, from which Yoga is derived, teaches that

the self is held in bondage to matter by virtue of ignorance

and illusion, and must free itself by reversing the evolution

of the world, to return to an original state of purity and

consciousness. This process is called de-phenomenalization,

and involves controlling and suppressing mental activity, and

ending one's attachment to material objects. Samkhya,

as systematized in the Verses on the Samkhya by

Ishvarakrishna, a Hindu philosopher who lived in the 4th

century CE (you read that right -- 600 years after Patanjali),

is a dualist philosophy, but its dualism is not of the

Western, Cartesian kind. The entire universe is divided

into two kinds of things, prakriti, which is composed

of material substances, and purusha, which is pure

consciousness or spirit. Now, that sounds like

Descartes, but there's a difference: Ishvarakrishna includes

mind, as well as body, in the category of prakriti.

Anything that engages in action, including mental activities,

counts as praktiri; purusha can only observe what is

going on. In his Great Courses lecture, Hardy offers the

analogy of a lame man (a paraplegic might be better) riding on

the back of a blind man: "praktiri can't see anything

and purushk can't do anything". Suffering (samsara)

occurs when purusha and praktiri become

entangled with each other.

The term yoga is derived from a Sanskrit

word meaning "union" -- as in the union of the individual self

with the cosmic, divine Self. It shares the same

Indo-European root word as the English word yoke

-- something that ties one thing to another. Yoga is the

means for joining body and mind with spirit, separating praktiri

from purusha. And the instructions for doing

that were set down in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.

It's those "turnings of thought" that cause

suffering, and there are five of them:

Patanjali also taught that, once they've

achieved sanadhi, yogis could gain supernatural powers,

like the ability to levitate, or read minds, or know the

future. That might all be fun, but the most important

lesson of Yoga is that Descartes was wrong: it's when you stop

thinking that you achieve true selfhood.

In

In  19th-century

America, some of the "Transcendentalists", like Emerson and

Thoreau, were interested in Yoga (Thoreau actually practiced

yoga during his time on Walden Pond), but the discipline was

really introduced to America by Swami Vivekananda, who

lectured in Chicago at the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Thereafter it was promoted by Pierre Bernard and his nephew

Theos Bernard, who established a center for Tantric Yoga at

the Clarkstown Country Club in Nyack, New York, in 1909.

The CCC, in turn, served as a kind of American base for Swami

Paramahansa Yogananda, the author of Autobiography of a

Yogi (1944), who toured America in the 1920s and

1930s. Subsequently, American

interest in yoga shifted back and forth between the

spiritual and the secular.

19th-century

America, some of the "Transcendentalists", like Emerson and

Thoreau, were interested in Yoga (Thoreau actually practiced

yoga during his time on Walden Pond), but the discipline was

really introduced to America by Swami Vivekananda, who

lectured in Chicago at the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

Thereafter it was promoted by Pierre Bernard and his nephew

Theos Bernard, who established a center for Tantric Yoga at

the Clarkstown Country Club in Nyack, New York, in 1909.

The CCC, in turn, served as a kind of American base for Swami

Paramahansa Yogananda, the author of Autobiography of a

Yogi (1944), who toured America in the 1920s and

1930s. Subsequently, American

interest in yoga shifted back and forth between the

spiritual and the secular.

outlined in the Kama Sutra.

Interest in the spiritual side of yoga was

stimulated by the publication of Somerset Maugham's

novel The Razor's Edge (1944). This

book, whose title is taken from the Hindu Upanishads,

focuses on Larry Durrell, an American veteran of

World War I, who (in part) seeks enlightenment and

spiritual renewal in India at an ashram run by Sri

Ganesha. Maugham's portrait of Ganesha, in

turn, was based on his own experience at an ashram

run by Sri Ramana Maharshi (pictured here), in

Tiruvannamalai, in Tamil Nadu [see "Somerset

Maugham's Swami" by David Shaftel, New York

Times Book Review, 07/25/2010).

outlined in the Kama Sutra.

Interest in the spiritual side of yoga was

stimulated by the publication of Somerset Maugham's

novel The Razor's Edge (1944). This

book, whose title is taken from the Hindu Upanishads,

focuses on Larry Durrell, an American veteran of

World War I, who (in part) seeks enlightenment and

spiritual renewal in India at an ashram run by Sri

Ganesha. Maugham's portrait of Ganesha, in

turn, was based on his own experience at an ashram

run by Sri Ramana Maharshi (pictured here), in

Tiruvannamalai, in Tamil Nadu [see "Somerset

Maugham's Swami" by David Shaftel, New York

Times Book Review, 07/25/2010). For details,

see:

An offshoot of Yoga meditation

is the program of Transcendental Meditation (TM)

promoted by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

(1917-2008). In some ways, TM represents both a

secularization and a commodification of Yoga: TM abandons much

of Hindu religious beliefs in favor of a more secular

philosophy of Vedanta, which emphasizes meditation

alone -- techniques that are taught for a fee in

classes. In TM, practitioners learn to meditate on a mantra,

a short word or phrase (e.g., om mani padme hum, or "om,

the jewel in the lotus, hum"), provided to them by

their Guru, in order to achieve deep relaxation, and

enhanced joy, vitality, and creativity. Like the Dalai

Lama, the Maharishi was very interested in psychology, and in

his Science of Creative Intelligence taught

that through TM, practitioners could achieve a higher stage of

cognitive development -- apparently, there's more to life

beyond Piagetian formal operations!).

For an account of the TM course taught in 1968 by Maharishi at his ashram in Rishikesh, and attended by the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Donavan, Mia Farrow, and other popular-culture figures, see "The Road to Bliss" by Mike Love (yes, that Mike Love), Smithsonian magazine, 01-02/2018.

There are lots of other traditions and schools, not the least of which is Zen Buddhism and the Tibetan tradition associated with the Dalai Lama.

But all of Buddhism, no matter what its tradition or school, begins with what the Buddha taught as the Four Noble Truths

Schopenhauer

Pursues the Four Noble Truths on the Eightfold Path

The German Romantic philosopher Arthur

Schopenhauer (1788-1860) was perhaps as much influenced by

the Buddha as he was by Plato or Kant. In fact, he

was arguably the first Western philosopher to be seriously

influenced by Hindu and Buddhist thought.

Schopenhauer believed that what appears to our sensory

apparatus is not the "Thing-in-Itself (Ding an Sich),

but only a representation of it. Shades of Plato and

his distinction between the Forms of things and the

shadows cast on the walls of the cave. Unlike Kant,

however, he did not believe that the Thing-in-Itself is

unknowable, but is knowable through the Will (excuse the

initial caps: he was German), by which he really means

constructive cognitive activity. Most important, for

our purposes, Schopenhauer believed that the world is a

pretty awful place, and existence too (Buddhist Connection

#1), and the awfulness of the world is not merely an

empirical fact but a necessary truth that follows from the

representational function of the Will (Buddhist Connection

#2). In his view, there are only two ways out of

this situation. First is a renunciation of the Will,

so that the person becomes a "pure, will-less subject of

the intellect" -- a Saint (Buddhist Connection #3).

Failing that, one should absorb oneself (see the lectures

on Absorption) in aesthetic experience -- the

experience of beauty being the closest most people get to

the ideal Platonic forms. But not just any aesthetic

experience, because the visual arts are representational

(Abstract Expressionism hadn't been invented yet), and

representations come from the Will, and that just leads to

more misery. The prescribed aesthetic experience is

music -- which, in Schopenhauer's view, doesn't represent

anything (apparently Schopenhauer hadn't heard Listz's

"tone poems", the first of which was written about 1859,

and other examples of Romantic-era "program music"), and

draws our attention away from objects in the world and our

representations of them. |

There are a lot more numbered lists in Buddhism (probably

because it was transmitted orally for so long, and list

structures make things easier to remember).

Anyway, the last three of the Eightfold Path

brings us to meditation, which plays a more important role in

Buddhism than in any other major religion, as it is the path

to nirvana.

All of this, in Buddhist doctrine, leads

ultimately to nirvana, and with it the extinction of both

desire and of individual consciousness.

Still, it's important to

understand that meditation, and the mindfulness that it

inculcates, is not all there is to achieving

nirvana, and ending suffering. There is also an ethical

code, consisting of what

might be called "The Six Rights" of the Eightfold Path: Right

Understanding, Right Motivation, Right Livelihood, Right

Action, Right Speech, and Right Effort. The whole thing

is a package, and meditation and mindfulness alone won't do

the trick.

If meditation is important to Buddhism, it is

especially important to Zen Buddhism, a form

originating in China in the 5th century CE, and imported to Japan in the 12th century, and to the United

States by Daisetz T. Suzuki (1870-1966). There are three major sects of Zen Buddhism,

differing mainly in their objects of concentration.

In addition to Zen, interest in Tibetan Buddhist meditation has been greatly stimulated stimulated by the undeniably charismatic Dalai Lama. Tibetan Buddhism, in turn, has been taken up by a number of researchers associated with the positive psychology movement.[A year after taking up Zen meditation] he attended his first multiday sesshin with a group of Zen meditators. The Rinzai teacher instructed him to "kill the watcher" within. By the third session he experienced kensho, which some meditators spend their lives hoping to attain: " I felt as if something like an earthquake or implosion was about to happen," he wrote in his autobiography. "Everything around me looked exceedingly odd, as if the glue separating things had started to melt.... By the time I got to my room I was weightless; there was no gravity.... Then the earthquake or implosion -- 'body and mind dropping off' -- occurred. There was an incredible explosion of light coming from inside and outside simultaneously, and everything disappeared into that light... there was no longer a here versus there, a this versus that.... I understood nothing except that nothing would ever seem the same to me.... And despite the fact that I had no understanding whatever of what had happened (nor do I now), this experience changed my life completely" ("How a Zen Master Found the Light (Again) on the Analyst's Couch" by Chip Brown, New York Times Magazine, 04/26/2009).

While Zen Buddhism is usually associated with inner serenity, compassion, and nonviolence, it can be very warlike -- an extension of the great demands it makes for mental discipline. As such, it has a dark history recounted by Brian Victoria, himself a Zen priest and historian, in Zen at War (1997) and Zen War Stories (2002). Victoria shows that Zen was long associated with the Japanese warrior culture, as a kind of romanticization of the samurai. Along with the state religion of Shinto, Zen formed the theological underpinnings for Japanese aggression in World War II: the self-denying egolessness of the Zen master became "fascist mind control", and acceptance of death justified killing and martyrdom -- as in the kamikaze pilots, and the treat of national suicide if the home islands were ever invaded. Of course, some of this also represented social conformity under political pressure. Doubtless, Zen was co-opted by the Japanese war machine, just as religions are everywhere from time to time (in World War II, some Catholic priests blessed American tanks).

All of which leaves us

with a number of different techniques, all of which go

under the label of "meditation". Antoine Lutz

(2008), a prominent contemporary meditation researcher,

identifies several basic kinds

of Buddhist meditation technique.

Based on both controlled research

and personal experience with meditation, Lutz et al. (2015) have

offered a 3-dimensional matrix for classifying various forms of

meditation and related experiences (including

mind-wandering). It looks a little like Hobson's AIM model,

introduced in the lectures on Sleep and Dreaming, but the

axes are different. Lutz's scheme consists of three

independent primary dimensions targeted by all

"mindfulness practices", such as meditation, and four secondary

qualities, which distinguish among various practices.

The primary qualities are considered orthogonal to, or independent of, each other:

The secondary qualities are also more or less independent of the primary qualities. You can think of them as four additional dimensions of mindfulness-related practices. It's just that, in visual terms, they're hard to plot in the three-dimensional space that's already taken up with the three primary qualities.

The point of all of this is that there are lots of different kinds of "meditation". When we try to bring meditation into the laboratory, to study is scientifically, it's important to be clear about what kind of meditation we are studying. Yoga practiced to achieve samadhi may be quite different in its effects than yoga practiced to achieve six-pack abs. Contemplating a Zen koan may have quite different effects than contemplating the suffering of the world.

Of

course, even diligent meditators

experience episodes of mind-wandering and daydreaming -- which is

one reason that Zen masters wield a keisaku, a wooden

stick which they use when a pupil falls asleep or otherwise drifts

off. Based on studies of the default mode network in

the brain, an fMRI study by Hasenkamp et al. examined brain

activity in a group of subjects practicing "one-point" or "focused

attention" meditation. The study is of particular interest

because it brings together two literatures: one on meditation as

mind-focusing, and the other on daydreaming as mind-wandering.

With increased

practice at meditation, these episodes become less frequent in

occurrence and shorter in duration.

Here's a nice depiction of the entire cycle, from "The Mind of

the Meditator" by M. Ricard, A. Lutz, and R.J. Davidson (Scientific

American, 11/2014). the implication of this study,

however, is that from a cognitive-neuroscientific point of view,

meditation is just a special case of focused attention --

different in quantity, perhaps, but not different qualitatively

from focusing attention on any other object of interest, such as a

symphony or a football game.

SourcesI'm not a scholar of world

religions. In these lectures, I'm

really only interested in placing meditation in its original religious

and cultural context. To that end, the

information in this section is drawn freely

from the Encyclopedia of World Religions,

edited by Wendy Doniger (1999), to which the

interested reader is referred for more

detail on these topics -- and indeed

concerning all things religious. I've also drawn on Great

Minds of the Eastern Intellectual

Tradition (2011), a set of 36 lectures

offered by Prof. Grant Hardy of the

University of North Carolina, Asheville as

part of the "Great Courses" series of

videos. See in particular, the

following lectures: 13. "Ishvarakrishna and Patanjali--Yoga. Students with a special interest in Buddhism are encouraged to take the course on Buddhist psychology offered by Prof. Eleanor Rosch and her colleagues; there are also relevant courses offered in the undergraduate interdisciplinary major in Religious Studies. For an account of a Vipassana Buddhist meditation, see two books by Tim Parks, himself a longtime practitioner:

|

This scientific research almost necessarily stripped meditation practices of their religious and cultural underpinnings. Arthur Deikman, Edward Maupin, and others sought to bring meditation in the laboratory by developing standardized procedures for concentrative meditation, and then inquiring into subjects' phenomenal experiences.

Deikman

(1963) asked subjects to concentrate on a blue vase

for 15 "nonanalytic, discursive" minutes, excluding

irrelevant thoughts (this isn't Deikman's vase, but it

will do for the purposes of illustration).

Across 12 such sessions, he played auditory messages

(music, prose, poetry, and even word lists) in the

background. His subjects reported changes in

their perception of the vase (e.g., its color and

shape); changes in the sense of time (i.e., that time

passed more quickly than usual), decreased

distraction, and increased "personal involvement" with

the vase.

Deikman

(1963) asked subjects to concentrate on a blue vase

for 15 "nonanalytic, discursive" minutes, excluding

irrelevant thoughts (this isn't Deikman's vase, but it

will do for the purposes of illustration).

Across 12 such sessions, he played auditory messages

(music, prose, poetry, and even word lists) in the

background. His subjects reported changes in

their perception of the vase (e.g., its color and

shape); changes in the sense of time (i.e., that time

passed more quickly than usual), decreased

distraction, and increased "personal involvement" with

the vase.

Ina

similar experiment, Maupin (1965) engaged subjects in

a Zen meditation exercise, in which meditators focused

on their breathing, rather than on an internal object,

for nine 45-minute sessions. He then classified

their responses into five categories:

Ina

similar experiment, Maupin (1965) engaged subjects in

a Zen meditation exercise, in which meditators focused

on their breathing, rather than on an internal object,

for nine 45-minute sessions. He then classified

their responses into five categories:

Although

Although

most of

Maupin's subjects experienced relaxation and

calmness, only relatively few achieved a state of

concentration and detachment. Perhaps inspired by

the assessment of hypnotizability, Maupin tried to

classify his subjects in terms of their response to

the meditation procedure. "Low" responders

experienced primarily fogginess and relaxation, while

"high" responders were also able to achieve some level

of detachment.

most of

Maupin's subjects experienced relaxation and

calmness, only relatively few achieved a state of

concentration and detachment. Perhaps inspired by

the assessment of hypnotizability, Maupin tried to

classify his subjects in terms of their response to

the meditation procedure. "Low" responders

experienced primarily fogginess and relaxation, while

"high" responders were also able to achieve some level

of detachment.

In a

pioneering attempt to correlated response to

meditation with something else, outside the domain of

meditation, Van Nuys (1973) instructed subjects to

concentrate on a candle, or on their breathing.

Subjects varied widely in terms of the number of

intrusive thoughts they experienced. This

variable correlated negatively with hypnotizability

(i.e., fewer intrusions were associated with high

hypnotizability), but not scores on the As Experience

Inventory, a forerunner to the Tellegen Absorption

Scale. The correlation with hypnotizability

probably means that subjects who can focus their

attention on a candle, or on their breathing, can also

focus their attention on the hypnotic

induction.

In a

pioneering attempt to correlated response to

meditation with something else, outside the domain of

meditation, Van Nuys (1973) instructed subjects to

concentrate on a candle, or on their breathing.

Subjects varied widely in terms of the number of

intrusive thoughts they experienced. This

variable correlated negatively with hypnotizability

(i.e., fewer intrusions were associated with high

hypnotizability), but not scores on the As Experience

Inventory, a forerunner to the Tellegen Absorption

Scale. The correlation with hypnotizability

probably means that subjects who can focus their

attention on a candle, or on their breathing, can also

focus their attention on the hypnotic

induction.

Research on meditation is potentially interesting, but from the perspective of modern experimental psychology, it entails some serious problems.

First and foremost, experimental psychologists like to employ the random assignment of subjects to conditions. This allows them to make strong inferences that the independent variable manipulated in the experiment really has a causal influence on the dependent outcome variable. But a meditative practice ripped from its philosophical, religious, and cultural underpinnings may not be the same as the same practice in its usual cultural context. After all, the goal of yoga or Zen meditation is expressly religious. Put another way: yoga meditation may have quite different effects on Hindus than on Presbyterians (or agnostics or atheists). The obvious problem, then is that while an experimenter can randomly assign subjects to focus their attention on a vase (the experimental group) or not (the control group), you can't assign subjects randomly to be Hindus or Buddhists.

Second, there is the problem of practice effects. The effects of meditation in neophytes may be quite different from those in experienced by experts. And it is possible that the effects of meditation differ depending on whether meditation is practiced in a religious-philosophical or secular-instrumental context.

At the very least, research needs to distinguish between three quite different types of effects of meditation

How to Meditate

Of course, if you're going to

study meditation, you've got to know how to meditate

in the first place. By now, there are a number

of commercial meditation programs out there, some of which are discussed below:

Transcendental Meditation, the Relaxation Response,

and Mindfulness Meditation.

The essence of all these meditative practices has been distilled by Andrew Newberg, a physician who has pioneered the study of neurotheology, or the application of neuroscientific techniques such as brain imaging to the study of religious practice and experience -- including various forms of prayer and meditation.

Setting these non-trivial problems aside, why should anyone want to do this research?

In Deikman's view, renunciation without contemplation is not effective. Contemplation without renunciation is not enough.

Both contemplation and renunciation are woven into a psychosocial system -- the theology, philosophy, or "culture" of Yoga, or Zen, or whatever, or even the affiliation with a particular master or guru -- intended to bring about the desired cognitive changes.

The object of the meditative exercise, according

to Deikman, is to shift from an action mode

entailing the manipulation of the environment to a

receptive mode of passive experience --

from doing things to letting things be.

Deikman (1966) summarized all

this with a single word: de-automatization:

a re-organization of cognitive structures, which

usually operate automatically, so that the

meditator looks at the self and the world in new

ways. Unfortunately, Deikman was ahead of

his time: although terms like "automatism" had

been around since the 19th century (as in the

early literature on hysteria), modern cognitive

psychology did not employ this term with a

rigorous technical definition until the

mid-to-late 1970s.

But setting aside the

philosophical and religious and mystical

implications of the meditative experience, looking

back from the perspective of modern cognitive

psychology and cognitive science, we can see what

the theoretical implications of meditation might

be. Usually, we think of automatization as

permanent. Whether the process is innately

automatic, or automatized through learning and

practice (proceduralization), the tacit

assumption has been that automaticity is

permanent. Once a process is automatized, it

stays automatized. But meditation offers the

possibility -- the hypothesis -- that

automatization is not permanent, and can be

reversed.

But setting aside the

philosophical and religious and mystical

implications of the meditative experience, looking

back from the perspective of modern cognitive

psychology and cognitive science, we can see what

the theoretical implications of meditation might

be. Usually, we think of automatization as

permanent. Whether the process is innately

automatic, or automatized through learning and

practice (proceduralization), the tacit

assumption has been that automaticity is

permanent. Once a process is automatized, it

stays automatized. But meditation offers the

possibility -- the hypothesis -- that

automatization is not permanent, and can be

reversed.

Early experiments on meditation involved either attempts to perform controlled, quantitative studies of religious practitioners, or attempts to develop laboratory models of meditation exercises which could be performed by novices.

Much of this work

has employed EEG measures, and much of the EEG

work has focused on alpha activity.

Much of this work

has employed EEG measures, and much of the EEG

work has focused on alpha activity.

Perhaps the most provocative of these early studies were two psychophysiological experiments on yoga and Zen meditation.

In the

yoga experiment, Anand et al. (1961) recorded EEG

activity in two experienced yogis, and in a larger

group of yoga students. They found increased

density of alpha activity during meditation.

In the

yoga experiment, Anand et al. (1961) recorded EEG

activity in two experienced yogis, and in a larger

group of yoga students. They found increased

density of alpha activity during meditation.

More interesting, however, they found no evidence of alpha blocking -- a reflexive orienting response in which alpha activity disappears when the subject orients to a novel stimulus. The abolition of the blocking response was interpreted as consistent with the goal of yoga meditation, samadhi, which is to become oblivious to environmental stimuli.

In the

Zen experiment, Kasamatsu & Hirai (1966)

studied Zen masters and students, all of whom were

practicing the classic zazen form of

meditation -- sitting, with eyes open and focused

in front.

In the

Zen experiment, Kasamatsu & Hirai (1966)

studied Zen masters and students, all of whom were

practicing the classic zazen form of

meditation -- sitting, with eyes open and focused

in front.

Again, they found increased alpha activity -- despite the fact that the subjects' eyes were open. Towards the end of the meditation periods, they also observed an increased density of EEG theta activity.

The

The  density of alpha activity

in the EEG was positively correlated with both

the amount of experience of the subject with

meditation, and with the master's evaluation of

the subject's progress in training.

density of alpha activity

in the EEG was positively correlated with both

the amount of experience of the subject with

meditation, and with the master's evaluation of

the subject's progress in training.

In contrast to yoga, however,they observed that alpha blocking to the novel stimulus was not abolished. To the contrary, alpha blocking did not habituate with continued presentations of the stimulus.

The persistence of blocking, and the abolition of habituation, was interpreted as consistent with the goal of Zen meditation, satori, which is to free the mind from preconceptions and be attuned to each new experience as it presents itself.

Both studies revealed an increase in slow-wave activity in the EEG: an increase in alpha density, a decrease (i.e., slowing) in the frequency of alpha activity, and an increase in theta activity. Of course, some of this could have been an artifact. Alpha activity increases when subjects close their eyes, and even with their eyes open, alpha increases when subjects are "not looking" at anything in particular. More important, taken together, the yoga and Zen studies seemed to show that the physiological effects of meditation were in line with the philosophical-religious goals of the discipline. Yogis seek to become oblivious to the world, and they don't respond to novel stimuli. Zen meditators seek to dissolve preconceived categories, and they don't habituate the alpha-blocking response.

Unfortunately, the findings

with respect to alpha blocking were not

confirmed in a replication attempt by Becker

& Shapiro (1980). Their study included

practitioners of traditional Yoga,

Transcendental Meditation (a secularized form of

Yoga -- see below) and Zen, as well as control

groups of nonmeditators who were instructed

either to attend to or ignore the stimuli. The

five groups performed essentially identically in

the experiment. although the meditators did show

an increase in EEG alpha activity, no group

showed any particular effect on alpha blocking

or on habituation. Failures to replicate are

surprisingly common in science, and this

discrepancy remains to be resolved by further

research.

Unfortunately, the findings

with respect to alpha blocking were not

confirmed in a replication attempt by Becker

& Shapiro (1980). Their study included

practitioners of traditional Yoga,

Transcendental Meditation (a secularized form of

Yoga -- see below) and Zen, as well as control

groups of nonmeditators who were instructed

either to attend to or ignore the stimuli. The

five groups performed essentially identically in

the experiment. although the meditators did show

an increase in EEG alpha activity, no group

showed any particular effect on alpha blocking

or on habituation. Failures to replicate are

surprisingly common in science, and this

discrepancy remains to be resolved by further

research.

One offshoot of the initial psychological interest in meditation has been research and clinical application of alpha-wave biofeedback. In biofeedback, information about the functioning of internal organs and systems, normally unavailable to conscious perception, is picked up electronically and fed to the person in the form of an auditory or visual signal. The person is then taught to engage in some activity which will alter the internal function, as reflected in changes in the signal. Research by Neal Miller indicated that nonhuman animals could learn to control levels of autonomic function through biofeedback (with physiological changes in the desired direction rewarded by electrical stimulation of the brain), and researchers and clinicians quickly came to apply biofeedback technology in the treatment of a host of physical, psychological, and psychosomatic problems.

In

In  a pioneering study,

Kamiya (1969) reported that subjects could learn

to discriminate levels of alpha activity (i.e.,

alpha density) in the EEG, and could also learn,

through biofeedback, to increase the levels of

alpha activity in their brains. The subjective

characteristics of the "alpha state" appeared to

resemble those of meditation, leading to the

peculiarly American idea that people could

achieve satori through technology rather

than through religious discipline.

a pioneering study,

Kamiya (1969) reported that subjects could learn

to discriminate levels of alpha activity (i.e.,

alpha density) in the EEG, and could also learn,

through biofeedback, to increase the levels of

alpha activity in their brains. The subjective

characteristics of the "alpha state" appeared to

resemble those of meditation, leading to the

peculiarly American idea that people could

achieve satori through technology rather

than through religious discipline.

Kamiya's initial report was subsequently confirmed by Nowlis & Kamiya (1970) and by Brown (1970), but critics soon discovered methodological problems with these studies that cast doubt on their conclusions and implications.

For example, the ability to

detect the presence of alpha activity may be an

artifact of response bias. Under ordinary

circumstances, as subjects habituate to the

experimental situation, alpha activity increases

over time. Therefore, if alpha density is

increasing, subjects who are biased to say they

are in the alpha state will be right more often

than wrong, just by chance. This is a situation

that signal-detection theory is able to

unconfound, but signal-detection theory requires

the presence of the stimulus (in this case,

alpha activity) to be under the control of the

experimenter -- which is not possible in the

case of endogenous EEG variables.

For example, the ability to

detect the presence of alpha activity may be an

artifact of response bias. Under ordinary

circumstances, as subjects habituate to the

experimental situation, alpha activity increases

over time. Therefore, if alpha density is

increasing, subjects who are biased to say they

are in the alpha state will be right more often

than wrong, just by chance. This is a situation

that signal-detection theory is able to

unconfound, but signal-detection theory requires

the presence of the stimulus (in this case,

alpha activity) to be under the control of the

experimenter -- which is not possible in the

case of endogenous EEG variables.

In addition, it is known that visual activity blocks EEG alpha, and that this blocking habituates over time. It is possible that the appearance of learning to increase alpha density reflects this habituation process. Alternatively, the appearance of learning could reflect nothing more than disinhibition of alpha produced by disengaging from looking activity.

A series of studies by Paskewitz and his associates (1969, 1971, 1973) found no evidence that subjects with their eyes open could learn to produce levels of alpha activity exceeding those observed in an eyes-closed baseline session. Furthermore, equivalent increases in alpha activity were found in a "yoked" control group of subjects who received the same feedback as the experimental group, regardless of their levels of EEG alpha. So, despite appearances, there appears to be no contingent learning in alpha biofeedback. Moreover, Paskewitz et al. found that subjective reports of the "alpha state" were influenced by demand characteristics of the biofeedback situation, a finding confirmed by Plotkin. Biofeedback may help people to gain control of certain autonomic functions, but brain-wave biofeedback does not appear to be a route to instant satori.

John's Excellent Adventure with ShibayamaAs an undergraduate, I read the Anand and Kasamatsu & Hirai studies of meditation, and Kamiya's initial report on alpha biofeedback, as reprinted in Charles Tart's pioneering anthology, Altered States of Consciousness (1969). I had determined that my senior honors thesis in psychology would be a replication of Tart's research.

A little background:

Anyway, I did not have room in my schedule to take Shibayama's seminar, but I had met him on a couple of occasions under the auspices of Chapel House, a meditative retreat center at Colgate where he was staying. So while I waited for the psychology department's technician to breadboard a biofeedback device, I set about attempting to replicate the Kasamatsu experiment -- on Shibayama (as it happened, the tech was unable to get the equipment working in time, so I did my thesis on hypnosis instead). In one of our meetings I described the research on Zen and Yoga practitioners, and later provided him with copies of the papers. His response on both occasions was "It's very interesting, but what does it mean?". Eventually, I screwed up my courage and asked him if he would allow an EEG recording while he meditated. Never mind that Rinzai Zen focuses on koans, not zazen! His response: "If the Pope were here, would you ask to record his brainwaves while he prayed?". When I admitted that I would not, he asked "Why not?". I had no answer, and that effectively ended the discussion. In The

Laughing Buddha of Tofukuji,

Ishwar Harris reports that, at one

point, Shibayama told Fukushima

(also known as Gensho) that he

should return to his university,

"implying that Gensho thought like

a scholar not like a koan

student". Perhaps Shibayama

was offering me similar

advice. But in retrospect, I

think that his question about the

Pope at prayer was my own little

koan -- and that when I solved it,

I would achieve at least a little

bit of enlightenment.

|

Binaural beats are an auditory

illusion. When two pure tones of

slightly different frequencies are presented

to each ear, their loudness appears to

fluctuate at a frequency equal to the

difference between them. So, for

example, if a tone of 440 hz is presented to

the left ear and a tone of 445 hz is presented

to the right ear, the tones will appear to

fluctuate at a rate of 5/second. They

were comprehensively described in an article,

"Auditory beats in the Brain", by Gerald

Oster, a biophysicist, that appeared in Scientific

American for October 1973.

These beats are familiar to any musician who

has tuned one instrument to another, but after

Oster's article appeared some 'New Age" types

began to make claims that these beats

"entrained" brain waves, and thus could

influence consciousness. So, for

example, it was claimed that beats in the

range of EEG alpha activity (roughly 8-14 cps)

would increase levels of alpha activity in the

brain, and thus induce a meditation-like state

(based on evidence that meditation also

produced an increase in alpha activity).

And "binaural beat generators" are sold by a

number of firms, for just this purpose.

But the scientific base for these claims is

very thin. A quick PsycInfo search

turned up only two articles bearing on the

question, both from the same research group

(Wahbeh et al), and published in the Journal

of Complementary Medicine for

2007. In the first study subjects who

got 60 days of binaural beats showed a

reduction in trait anxiety. The second

study had something like a placebo control

group: it didn't measure anxiety, but the

subjects did show an increase in

depression. That's it. That's the

scientific base.

I'm sure that there's a placebo effect here --

frankly, there's a placebo effect in almost

every treatment!

But, like alpha-wave biofeedback, I suspect that the attraction of binaural beats is that they offer another way to achieve "instant satori -- enlightenment without all the hassle of disciplined contemplation.

Meditation was originally imported to the West, and first came to scientific attention, in an explicitly philosophical-religious context: Hinduism and Vedic philosophy for Yoga, Buddhism for Zen. A more recent trend, however, has been to strip away the religious-philosophical aspects of meditative practice, and to teach meditation, for a fee, in a secular context as a means of self-improvement -- for example, as a form of physical exercise or a means of stress-reduction.

A great deal of

meditation research has involved

Transcendental Meditation (TM), a

commodified (trademarked and commercialized)

offshoot of Yoga meditation developed by the

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and popularized by him

and his followers as the "Science of Creative

Intelligence", based on the Indian philosophy

of Vedanta, which forms the basis of

Hinduism. Its major texts are the Upanishads,

the Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad

Gita. Although the focus of TM is

on meditation technique rather than any

particular set of religious or philosophical

beliefs, and TM can be (and is) practiced by

people who hold a wide variety of religious

beliefs (or none), TM retains a

quasi-religious character -- especially in the

"TM-Sidhi" program.

Later, TM was fully

secularized by Herbert Benson, a psychiatrist

at Harvard Medical School, in the form of the

"relaxation response", and promoted as a means

of achieving cardiovascular health.

Later, TM was fully

secularized by Herbert Benson, a psychiatrist

at Harvard Medical School, in the form of the

"relaxation response", and promoted as a means

of achieving cardiovascular health.

Proponents of both TM and

The Relaxation Response have generated a large

body of laboratory research. However,

these experiments have focused mostly on the

physiological effects of meditation, which

resemble those of profound (but alert, not

sleep-like) relaxation (e.g., Wallace &

Benson, 1972). There have been very few

studies of the cognitive effects of

meditation.

Proponents of both TM and

The Relaxation Response have generated a large

body of laboratory research. However,

these experiments have focused mostly on the

physiological effects of meditation, which

resemble those of profound (but alert, not

sleep-like) relaxation (e.g., Wallace &

Benson, 1972). There have been very few

studies of the cognitive effects of

meditation.

For example, Dillbeck

& Orme-Johnson (1987) found that TM

significantly modulated various physiological

measures of stress, compared to a control

period in which subjects merely rested.

For example, Dillbeck

& Orme-Johnson (1987) found that TM

significantly modulated various physiological

measures of stress, compared to a control

period in which subjects merely rested.

In much the same way, the

principles of Buddhist meditation (primarily

Zen, but not exclusively) have been

secularized in the form of Mindfulness-Based

Stress Reduction (MBSR) by John

Kabat-Zinn, a clinical psychologist at the

University of Massachusetts School of

Medicine. MBSR is expressly presented as a

secularized derivative of Buddhist practice,

intended to achieve a state of

"moment-to-moment nonjudgmental awareness" as

a means of reducing the stress of everyday

living.

MBSR is operationally defined -- that is, defined by the operations that produce it -- as follows:

As with the Relaxation

Response, MBSR is intended as a method of

stress-reduction, and not necessarily for

consciousness-raising or

de-automatization. Accordingly, most of

the empirical research on MBSR has focused on

its physiological effects on measures related

to stress such as heart rate and blood

pressure. Outcomes have also been measured in

terms of reported mood and anxiety. This is

quite reasonable, as MBSR has its origins as a

stress-reduction technique. Any cognitive

changes produced by MBSR are intended to "end

suffering", and so the effectiveness of the

technique has generally been measured in terms

of its effects on stress and emotion --

whether these effects are measured

psychometrically or psychophysiologically.

Bishop et al. (2004) have proposed a two-component model of mindfulness.

These outcomes are often measured by the usual sorts of psychometric instruments.

The Toronto Mindfulness Scale (Lau et al., 2006) yields two scales intended to tap the subject's experience during meditation.

Take the Toronto Mindfulness ScaleIf you practice meditation, you might want to complete the TMS after your next session. If you don't practice meditation, you might want to complete it the next time you're daydreaming, or watching Dancing with the Stars. Link to a page containing the TMS and scoring instructions. |

In contrast to the "state" measurements of the TMS, the Five-Facet Mindfulness Scale (Baer et al., 2006, 2008) offers a somewhat more "trait-like" ted assessment of the consequences of meditative practice.

Take the Five-Facet Mindfulness ScaleThis scale is intended to measure the stable, long-term consequences of mindfulness meditation practice. However, it can also be used as a kind of personality scale, just like the Tellegen Absorption Scale or the Short Imaginal Processes Inventory, or the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. Link to a page containing the FFMS and scoring instructions. |

One example of the popularization of mindfulness meditation has

been the proliferation of smartphone application software (apps)

for mindfulness meditation. Among the most popular of these is

Headspace (for iPhone); also buddhify, Calm, Insight Timer, and

GPS for the Soul. A subscription to Headspace costs

$13/month (2015 prices), and supplies meditation "packs" on

various topics. For a discussion of Headspace, see "The

Higher Life" by Lizzie Widdicombe, New Yorker,

07/06-13/2015.

Another example of the secularization and commodification of Buddhist meditative techniques may be found in business management. Many large firms, especially high-tech firms centered on silicon Valley, now promote mindfulness-based meditation to their managers and other employees -- not necessarily for stress reduction, but rather to "disconnect to connect", and short-circuit the "rat-race" that comes along with high-powered business enterprises. This, in turn, has fostered the development of a whole new service industry -- namely, providing meditation training to these corporations. The stated goal of this meditation practice is to give the practitioner a competitive advantage. Now, here's a paradox. It's not clear that the goal of Buddhist meditation is stress-reduction, except indirectly, as a byproduct of clearing one's mind of habitual patterns of thought -- any more than that the goal of yoga is physical exercise (except as a path toward clearing one's mind). But, just as the primary purpose of yoga is not to trim your butt or flatten your abs, it's pretty clear that the goal of Buddhist medication is not to enhance one's competitiveness in the high-powered business environment characteristic of Western capitalism!

recall

that, according

to Deikman (1966),

the mystical experiences associated with

meditation have a number of different

facets, including reality transfer,

sensory translation, a unity between self

and object, ineffability, and

de-automatization. Only later, however,

did psychology and cognitive science

develop a full-blown

technical concept of automaticity,

providing a framework

for measuring the effects of meditation.

The question, then is whether

automaticity, once achieved, is permanent

-- or whether it is possible, through

meditation or any other means, to gain (or

regain)

conscious, voluntary control over some

automatic, unconscious process.

Perhaps, as well, the

answer will depend on how the process

has been automatized

in the first place. Processes

which have been automatized through

repeated practice may be easier to

de-automatize than those which are

innately automatic. Though,

still, that's a hypothesis.

Alpha Blocking, Startle, and Binocular Rivalry

Although they did

not invoke the concept, the early

studies of EEG alpha activity in yoga

and zen described earlier bear on the

question of de-automatization.

Recall that, in addition to their general

finding of increased levels of alpha activity,

Anand et al. (1961) and

Kasamatsu & Hirai (1966) found that

meditation altered the alpha-blocking orienting response: yogis did not show alpha

blocking to a novel stimulus, consistent

with the goal of yoga meditation to

become oblivious to the outside world;

and zen practitioners did not habituate

alpha-blocking to repeated presentations

of the novel stimulus, consistent with

the goal of Zen meditation to treat

every event as novel.

Unfortunately, as noted earlier,

Becker and Shapiro (1981) failed to

replicate either of these effects: yoga and

zen practitioners

showed the

same patterns of EEG activity,

and these were no different

from controls. Still, it was a

nice idea -- and maybe worth

following up on.

Some subsequent investigators have also pushed the limits of de-automatization, looking at the effects of meditation on hard-wired, reflexive responses to stimulation.

Levenson,

Ekman, and Ricard

(2012) performed

a study of

acoustic startle

in one Tibetan

Buddhist monk

(Ricard himself,

who also holds a

PhD in

biochemistry)

with 40 years' experience in

meditation. During the experiment (which seems almost

as Spartan as the study by Stern et al. of

hypnotic analgesia discussed in the

lectures on Hypnosis),

Ricard (and a group of nonmeditator controls) went

through six startle trials under each of 4

different conditions: That's a total

of 24 trials involving a brief "blast" of

white noise sounding not a little like a

gunshot.

A

study by Carter, Presti, and

their colleagues (2005) , employing a large number of Tibetan

monks and other experienced meditators, employed another automatic

behavior, binocular rivalry. In the BN paradigm,

subjects are presented with two different images to each eye --

one a horizontal, the other a vertical grating. Normally,

the visual system would fuse the separate 2-dimensional retinal

images into a single 3-dimensional image, but with such radically

disparate images this is impossible. Instead, the subject

experiences a random alternation between the images. This

phenomenon occurs automatically -- it's caused by a hard-wired

feature of the visual system. But, it turns out, one-point

meditation essentially abolishes binocular rivalry. During

meditation, a majority of subjects experienced a slowing of the

rate of alternation, and some subjects experienced a stable

image. Even after the meditation period had ended, half the

subjects continued to experience a slower rate of alternation --

though some showed a kind of rebound effect, alternation at an

even faster rate. Compassion meditation, by contrast, had no

effects at all on BN. That meditation can modulate something

as hired-wired as binocular rivalry is pretty interesting -- as is

the fact that the two types of meditation studied in this

experiment had quite different effects.

De-automatization

entails the reorganization of cognitive

schemata so that habitual modes of thought

no longer operate automatically, and it is

possible to view the world in other

ways. When Deikman introduced the

concept of de-automatization, psychology

did not have a technical concept of

automaticity. Now that it has one.

Automatic processes are defined as those

that are inevitably executed in response

to some cue, incorrigibly executed, and

consume no cognitive capacity. With

such a definition in hand, it becomes

possible, at least in principle, to

determine whether training in a meditative

discipline really does de-automatize

cognitive processing. Arguably,

the gold standard test of automatization,

and thus of de-automatization, would be

performance on the Stroop color-word

interference test (or some variant on the

Stroop paradigm). But investigators have

also employed other paradigms in the quest

to document de-automatization.

De-automatization

entails the reorganization of cognitive

schemata so that habitual modes of thought

no longer operate automatically, and it is

possible to view the world in other

ways. When Deikman introduced the

concept of de-automatization, psychology

did not have a technical concept of

automaticity. Now that it has one.

Automatic processes are defined as those

that are inevitably executed in response

to some cue, incorrigibly executed, and

consume no cognitive capacity. With

such a definition in hand, it becomes

possible, at least in principle, to

determine whether training in a meditative

discipline really does de-automatize

cognitive processing. Arguably,

the gold standard test of automatization,

and thus of de-automatization, would be

performance on the Stroop color-word

interference test (or some variant on the

Stroop paradigm). But investigators have

also employed other paradigms in the quest

to document de-automatization.

An early laboratory study by Dillbeck (1982) compared two different groups of TM practitioners against a non-meditating control group. One group "N/TM", waited for two weeks prior to initiating TM training; another group, "R/TM" practiced passive relaxation for two weeks prior to TM.

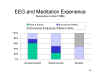

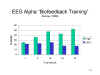

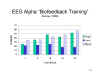

|

|

|

|

|

Later work by Alexander et al. (1989) suggested that TM could improve cognitive functioning in the elderly. This study involved a group of elderly residents of a retirement home, who practiced TM for 20 minute sessions, twice daily, for 12 weeks. Control groups engaged in a "mindful", guided attention activity intended to foster "new and creative" ways of thinking; mental relaxation; or nothing at all.

From time to time,

meditation researchers have employed other

tasks to study the

effects of meditation on various aspects

of cognitive and emotional processing

(for an overview, see Ricard et al.,

"Mind of the Meditator", Scientific

American, 11/2014).

Meditation and the Stroop Task

As

As

noted

earlier, the Stroop task is widely considered to be the primary exemplar

of automatic processing. The

study by Alexander et al. (1989)

did, in fact, find that TM

reduced Stroop interference. Unfortunately,

however, that reduction did not reach

statistical significance.

However, a doctoral

dissertation by Heidi Wenk-Sormaz (2006)

Systematic research by Wenk-Sormaz did

find that a "mindfulness" meditation

exercise reduced Stroop interference

(unlike many meditation researchers, who

tend to be trained in clinical psychology,

Wenk-Sormaz was trained as a cognitive

psychologist). Her subjects, who were

adult professionals participating in a

short course on meditation, practiced a

15-minute exercise in which they focused

on their breathing. This study was

conducted before MBSR became popular, but

the procedure was very similar to that

employed in MBSR. Wenk-Sormaz assessed

performance on the standard Stroop task

before and after meditation.

So, the

Wenk-Sormaz study shows that, indeed,

meditation can lead to the

de-automatization of thought.

meditation reduced Stroop interference

that was not an artifact of relaxation

or arousal. And it reduced habitual

categorization, when such a reduction

was optimal. These effects were

produced by a secularized

meditation technique, which no

theological or cultural overlay, to

which naive subjects were randomly

assigned. All the more interesting,

the effects were produced after only 15

minutes of meditation. By

contrast, the MBSR studies employed

subjects who had practiced meditation

for six to eight weeks.

In another study,

this one employing MBSR,

Anderson et al. (2007) tested a

group of subjects with no prior

experience with meditation, who

completed a standard eight-week

course in MBSR (a control group

did not meditate). He then

administered a number of

measures of stress and mood,

including the Positive and

Negative Affect Scales, the Beck

Depression and Anxiety

Inventories, and other

instruments. Examining post-test

changes from a pre-test

baseline, these investigators

found that more subjects in the

meditation group showed changes

in the "beneficial" direction:

more positive affect, less

negative affect, less

depression, and less

anxiety. Anderson et al.

also administered a number of

cognitive tasks, including the

standard and emotional versions

of the Stroop interference task,

an Object Decision Task, and a

Continuous Performance Test of

sustained attention and

attentional switching, but found

no effects of meditation.

In another study,

this one employing MBSR,

Anderson et al. (2007) tested a

group of subjects with no prior

experience with meditation, who

completed a standard eight-week

course in MBSR (a control group

did not meditate). He then

administered a number of

measures of stress and mood,

including the Positive and

Negative Affect Scales, the Beck

Depression and Anxiety

Inventories, and other

instruments. Examining post-test

changes from a pre-test

baseline, these investigators

found that more subjects in the

meditation group showed changes

in the "beneficial" direction:

more positive affect, less

negative affect, less

depression, and less

anxiety. Anderson et al.

also administered a number of

cognitive tasks, including the

standard and emotional versions

of the Stroop interference task,

an Object Decision Task, and a

Continuous Performance Test of

sustained attention and

attentional switching, but found

no effects of meditation.

On

the other hand, a later study of

MBSR by Moore and Malinowski

(2009) compared a group who

completed a six-week "beginner's

course" in MBSR with a group of

non-meditating controls on a

number of tests of cognitive

flexibility. They found small

effects on Stroop performance, but

no effects on the "D2"

Concentration and Endurance Test,

which provides multiple measures

of attention.

On

the other hand, a later study of

MBSR by Moore and Malinowski

(2009) compared a group who

completed a six-week "beginner's

course" in MBSR with a group of

non-meditating controls on a

number of tests of cognitive

flexibility. They found small

effects on Stroop performance, but

no effects on the "D2"

Concentration and Endurance Test,

which provides multiple measures

of attention.

It

It

should

be remembered, in passing, that meditation is not

necessarily unique in this respect. Raz and his

associates (e.g., 2002) found that a posthypnotic

suggestion for agnosia or alexia, in which the

stimulus words would appear as symbols in an

unfamiliar foreign language, actually eliminated

Stroop interference. Even eight weeks of meditation

training didn't accomplish that. Of course, the

subjects had to highly be hypnotizable, while the

meditation studies employed samples that were

arguably more representative of the population at

large. But the Raz studies do show what can be

accomplished in terms of de-automatization.

should

be remembered, in passing, that meditation is not

necessarily unique in this respect. Raz and his

associates (e.g., 2002) found that a posthypnotic

suggestion for agnosia or alexia, in which the

stimulus words would appear as symbols in an

unfamiliar foreign language, actually eliminated

Stroop interference. Even eight weeks of meditation

training didn't accomplish that. Of course, the

subjects had to highly be hypnotizable, while the

meditation studies employed samples that were

arguably more representative of the population at

large. But the Raz studies do show what can be

accomplished in terms of de-automatization.

By asking whether automatization is reversible, meditation research gains considerable theoretical significance. Implicit in the standard concept of automaticity is the idea that automaticity, whether innate or achieved through extensive practice, is permanent. By contrast, meditation research seems to indicate that automatization can be reversed

The flame of the alpha-biofeedback movement sputtered and went out, but the popularity of TM and the Relaxation Response, not to mention the injection of Zen Buddhism into popular culture, has kept interest in meditation at a high level.

And with the advent of more sophisticated technologies for brain imaging, we have begun to see a new wave of studies of brain activity during meditation -- with two differences:Davidson, Kabat-Zinn, and their colleagues (2003) recruited the employees of a local biotechnology firm for an experiment in which some would be randomly assigned to receive training in Kabat-Zinn's "mindfulness-based stress reduction program", and others served as a wait-list control. The meditators were taught MBSR in classes that met for 2-1/2 to 3 hours, once a week, for eight weeks, including a 7-hour silent retreat during Week 6. They also practiced MBSR at home for 1 hour/day, 6 days/week, with the help of guided audiotapes. EEG data was collected at baseline and at the conclusion of the 8-week period, during which the subjects were asked to narrate positive and negative life experiences.

Examining

Examining

the power of

alpha activity in the EEG, these

investigators detected a significant

shift to the left cerebral

hemisphere in the meditation

group.This finding takes its

significance in the context of prior

research by Davidson and his

colleagues indicating that emotional

states differentially activate the

cerebral hemispheres. To make

a long story short:

the power of

alpha activity in the EEG, these

investigators detected a significant

shift to the left cerebral

hemisphere in the meditation

group.This finding takes its

significance in the context of prior

research by Davidson and his

colleagues indicating that emotional

states differentially activate the

cerebral hemispheres. To make

a long story short:

Along

Along

these lines, Davidson,

Kabat-Zinn, et al. found that meditation increased left-PFC

activation during a positive emotion induction: controls activated

the left hemisphere too, but meditators increased LPFC even

more. Further, meditation produced L-PFC activation even

during a negative emotion induction -- in contrast to the

controls, who showed the usual shift to the right associated with

negative emotionality.

these lines, Davidson,

Kabat-Zinn, et al. found that meditation increased left-PFC