Social cognition is the study of how we understand the social world -- how we perceive, remember, and think about ourselves, other people, the situations in which we encounter them, and the behavior that takes place in them. As its name implies, social cognition stands at the intersection of cognitive and social psychology.

Psychology

is

the science of mental life -- so said William James, in the

first sentence of his Principles of Psychology

(1890). Psychologists study the cognitive, emotional, and

motivational structures and processes that underlie human

experience, thought, and action.

Psychology

is

the science of mental life -- so said William James, in the

first sentence of his Principles of Psychology

(1890). Psychologists study the cognitive, emotional, and

motivational structures and processes that underlie human

experience, thought, and action.

Psychology

is based on the doctrine of mental causation.

Accordingly,

psychology seeks to understand the mental structures and

processes that underlie behavior:

Cognitive

psychology, as a subdiscipline of psychology, is concerned

with cognitive structures and processes. The domain of

cognition ranges very widely.

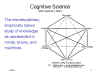

Cognitive

psychology

is an important component of cognitive science, which is

the interdisciplinary, empirically based study of knowledge

-- that is, the acquisition, representation, and use of

knowledge by minds and brains, machines and societies.

Cognitive psychology joins philosophy, linguistics, computer

science (artificial intelligence), neuroscience, and

anthropology (and other social sciences) to make up what Howard

Gardner (1985) has called the cognitive hexagon.

Cognitive

psychology

is an important component of cognitive science, which is

the interdisciplinary, empirically based study of knowledge

-- that is, the acquisition, representation, and use of

knowledge by minds and brains, machines and societies.

Cognitive psychology joins philosophy, linguistics, computer

science (artificial intelligence), neuroscience, and

anthropology (and other social sciences) to make up what Howard

Gardner (1985) has called the cognitive hexagon.

Social

psychology is often defined as the study of social

influence -- "how the thought, feeling, and behavior of

individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied

presence of other human beings" (G. Allport, 1954).

Indeed, a great deal of social-psychological research concerns

the study of social influence, as in the classic studies of

conformity and persuasion. But this is too narrow a

conception of the field, because it construes the individual

merely as a passive receptacle of influences coming from the

outside. I prefer the definition expressed by the title of

an early textbook in social psychology, written by three

professors from Berkeley: "The Individual in Society" (Krech,

Crutchfield, & Ballachey, 1948).

In formal terms, we can define social psychology as the study of the relation between an individual's internal mental structures and processes, and the structures and processes in the external, social world.

Put

another way, social psychology is the study of the relation

between the individual's experience, thought, and action -- what

the person is thinking, feeling, wanting, and doing -- and what

is going on in his or her wider social environment -- what other

people are thinking, feeling, wanting, doing, as well as the

activities of larger social and cultural structures.

There are

two primary aspects to social cognition:

This course emphasizes the second aspect (though it does not ignore the first). Accordingly, it looks a lot like a cognitive psychology course -- except that the objects of cognition are social in nature.

Social

perception entails the formation of a mental

representation of the stimulus situation. Information must

be extracted from the stimulus, and then combined with

information retrieved from memory. This process is

sometimes known as impression formation.

Social

memory concerns the acquisition, storage, and retrieval of

social knowledge. Social memory is often studied in the

form of person memory, or our memory for the

characteristics and behaviors of other people. However,

the self can also be construed as a social knowledge

structure stored in memory.

Social

thought and reasoning includes the principles that govern

how we make inferences, form judgments, and make choices in the

social domain.

Language

is a reflection of the mind, and a powerful tool for human

thought, but it is also an important means of human

communication. Accordingly, we need to understand how

social knowledge is represented, and shared,

linguistically.

Learning

is the process by which knowledge about ourselves and others is

acquired.

Intelligence is usually defined in terms of individual differences in cognitive ability: some people are just smarter than others, some people are good at math but bad at language, some the reverse. In some respects, the study of social cognition is really the study of social intelligence (Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987, 1989; Kihlstrom & Cantor, 1989, 2000). By social intelligence we don't mean "social IQ" -- the question of whether some people have more "social smarts" than others. The social intelligence viewpoint construes social behavior as intelligent behavior -- not the product of reflex, conditioned response, and genetic programming, but rather a product of the person's mental representation of the social situation, and his reasoning about that situation. Our mental representations of both social situations are constructed through our cognitive processes -- processes of perception, memory, thought, and language; they result from the application of declarative and procedural social knowledge -- our fund of facts and beliefs about the social world, and our repertoire of social skills and rules. From this point of view, individual differences in social behavior are not the product of personality traits. Rather, they reflect individual differences in social intelligence that individuals bring to bear on their social interactions.

Social-Cognitive

Development concerns the acquisition of social-cognitive

knowledge and skills, especially during childhood, and broaches

the "nature-nurture" question: how much social cognition is

innate, and how much is acquired through learning.

Social-Cognitive Neuropsychology and Neuroscience is now a major growth industry within social psychology. Beginning in the 1970s, researchers in (nonsocial) cognition began to take interest in neurological syndromes, such as amnesia and visual agnosia, for the light they could shed on basic processes of perception and memory. Similarly, social psychologists are turning to various syndromes, such as autism and prosopagnosia, for what they can tell us about the theory of mind and face recognition. Together with brain-imaging techniques such as PET and fMRI, these kinds of studies shed light on the neural bases of social cognition.

Social Constructivism plays an important role in cognitive social psychology. The idea that cognitive psychology is concerned with how we know the world suggests that the world, present and past, exists independently of the knower, And so it does. Nevertheless, from a psychological point of view it is clear that perception involves more than extracting information from a stimulus, and memory involves more than encoding, storing, and retrieving memory traces. In perception (in J.S. Bruner's apt phrase), we go "beyond the information given" by the stimulus to construct a mental representation of the environment based on inferences from world-knowledge. And in memory, following F.C. Bartlett, we appear to reconstruct events -- again, based as much on inference than on retrieval. Whether we are dealing with nonsocial or social objects and events, cognition isn't just about knowing reality; it's also about creating reality.

Psychology is a component discipline in interdisciplinary cognitive science, and each of the other component also has a contribution to make in understanding social cognition.

Of

particular interest is the development of cognitive perspectives

in other social sciences, such as anthropology, sociology, and

economics.

While all

forms of cognitive psychology, including social cognition, are

interested in how the individual comes to know reality through

the application of cognitive processes, it quickly becomes clear

that individuals can also create reality through those

same processes.

The study of social cognition can be organized like any course in cognitive psychology:

As a starting point, the study of social cognition assumes that people are objects, just like any other objects, and that the principles governing nonsocial perception, memory, and other aspects of cognition -- principles derived from the analysis of perceptual illusions, for example, verbal learning, or analogical reasoning -- also apply in the social domain.

This is a good first assumption, as it allows us to get the study of social cognition going, but we know that it isn't really true -- that there are important differences between the social and nonsocial worlds, and thus that there are important differences between social and nonsocial cognition.

Some of these differences

between social and nonsocial cognition are quantitative in

nature -- that is, differences in degree.

Some of these differences

between social and nonsocial cognition are quantitative in

nature -- that is, differences in degree.

For these reasons, the perceiver must, in Jerome Bruner's phrase, "go beyond the information given" by the stimulus, and fill in the gaps and resolve the ambiguities by making inferences about the stimulus given his knowledge, expectations, and beliefs. This is the expressly cognitive contribution of the perceiver to perception.

Consider, for example, the common problem of perceiving size and distance. In the Ames Room illusion, the three men appear to vary radically in height. But do they really? Given the size-distance rule, which states that there is an inverse relation between the size of an object and its distance from the viewer, the man at the left may be very small, or he may be very far away.

But when we view an object in the context of the Ames room, the arrangement of floor, ceiling, walls, windows, and doors provide a context that tells us that he is as close to us as the man on the right. Therefore, we conclude that the man on the left is exceptionally short, and the man on the right is exceptionally tall (the man in the middle seems "just right").

In the social case, we confront a similar

problem. If in the Ames Room we want to know where the

people are, and how big they are, in this picture (drawn from

the Thematic Apperception Test devised by H.A. Murray and his

colleagues), we want to know what the person is doing.

Obviously, he's looking at a violin. But is he? Are

his eyes open or closed? Beyond that, we want to know that

the boy is thinking, feeling, and desiring. Is this the

young Yehudi Menuhin, the musical prodigy, thinking about a Bach

sonata before he goes on stage to play before the crowned heads

of Europe? Of is this a kid who is supposed to be

practicing, but would rather be outside playing stickball with

his friends? Is this a boy who wants to play well, but

just doesn't have the talent? We don't know for

sure. The stimulus is ambiguous. But perhaps if we

had a little more context, we'd be able to figure it out.

In the social case, we confront a similar

problem. If in the Ames Room we want to know where the

people are, and how big they are, in this picture (drawn from

the Thematic Apperception Test devised by H.A. Murray and his

colleagues), we want to know what the person is doing.

Obviously, he's looking at a violin. But is he? Are

his eyes open or closed? Beyond that, we want to know that

the boy is thinking, feeling, and desiring. Is this the

young Yehudi Menuhin, the musical prodigy, thinking about a Bach

sonata before he goes on stage to play before the crowned heads

of Europe? Of is this a kid who is supposed to be

practicing, but would rather be outside playing stickball with

his friends? Is this a boy who wants to play well, but

just doesn't have the talent? We don't know for

sure. The stimulus is ambiguous. But perhaps if we

had a little more context, we'd be able to figure it out.

Here's

another

example: a famous (or, perhaps infamous) photograph

taken on the Brooklyn Esplanade on September 11, 2001. The

photographer, Thomas Hoepker of Magnum Photos, encountered the

group, took the picture, and went on to take other pictures

elsewhere. But because the photograph didn't "feel right",

and was "ambiguous and confusing", he put it in his file of

rejected images. Only later was the photograph made

public, principally in Watching the World Change: The

Stories Behind the Images of 9/11 by David Friend

(2006). Commenting further, Hoepker wrote that the group

"seemed totally relaxed like any normal afternoon. They

were just chatting away. It's possible they lost people

and cared, but they were not stirred by it.... I can only

speculate [but they] didn't seem to care".

Here's

another

example: a famous (or, perhaps infamous) photograph

taken on the Brooklyn Esplanade on September 11, 2001. The

photographer, Thomas Hoepker of Magnum Photos, encountered the

group, took the picture, and went on to take other pictures

elsewhere. But because the photograph didn't "feel right",

and was "ambiguous and confusing", he put it in his file of

rejected images. Only later was the photograph made

public, principally in Watching the World Change: The

Stories Behind the Images of 9/11 by David Friend

(2006). Commenting further, Hoepker wrote that the group

"seemed totally relaxed like any normal afternoon. They

were just chatting away. It's possible they lost people

and cared, but they were not stirred by it.... I can only

speculate [but they] didn't seem to care".

Friend's book was published in 2006, and on the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks Frank Rich, a columnist for the New York Times, wrote (09/10/06) that "Traumatic as the attack on America was, 9/11 would recede quickly into history. This is a country that likes to move on, and fast. The young people... aren't necessarily callous" -- implying, of course, that they were very callous indeed.

David Plotz, looking at the same photograph, had another interpretation: in Slate (09/11/06), he wrote that "they have turned toward each other for solace and for debate". He then called on the individuals pictured in the photograph to write to Slate and give their perspective on the picture.

One of the group, Walter Sipser (rightmost in the photo), responded that "[we were] a bunch of New Yorkers in the middle of an animated discussion about what had just happened".

Another, Chris Schiavo (the woman to the left of Spicer), wrote that her mother had been secretary to the architect of the Twin Towers, and that "it was genetically impossible for me to be unaffected by the event".

Still, without the testimony from the people themselves, it's not at all clear whose interpretation was right -- Rich's or Plotz's.

For more details, see "Time Capsule: Rediscovered 9/11 Picture Sparks Debate" by Daryl Lang, PDN Online, 09/15/06, from which these quotations are taken. The article has links to Rich's and Plotz's columns, Sipser and Schiavo's responses, and Hoepker's response.

Here's another one: the famous "Muskie

Moment" during the New Hampshire presidential primary in

February 1972. Edmund S. Muskie, then a senator from Maine

and a leading Democratic candidate for president, visited the

offices of the (famously conservative) Manchester

Union-Leader to complain about an extremely harsh

editorial the newspaper had published about his wife. This

photo was taken during Muskie's press conference on the steps of

the newspaper offices. David Broder, writing in the Washington

Post, described Muskie as in tears. Muskie's staff

responded that it was just snow melting on his face. But

the "tears" description stuck, implying weakness, and Muskie's

prospects for the presidency were dashed.

Here's another one: the famous "Muskie

Moment" during the New Hampshire presidential primary in

February 1972. Edmund S. Muskie, then a senator from Maine

and a leading Democratic candidate for president, visited the

offices of the (famously conservative) Manchester

Union-Leader to complain about an extremely harsh

editorial the newspaper had published about his wife. This

photo was taken during Muskie's press conference on the steps of

the newspaper offices. David Broder, writing in the Washington

Post, described Muskie as in tears. Muskie's staff

responded that it was just snow melting on his face. But

the "tears" description stuck, implying weakness, and Muskie's

prospects for the presidency were dashed.

And here's another 'Muskie Moment", from

the New Hampshire presidential primary of January 2008.

Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton (D-NY), then in a neck-and-neck

battle with Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) was asked at an event in

a diner (New Hampshire is famous for these) how she kept up the

rigors of a campaign. Clinton's eyes welled up, her voice

broke, and she seemed on the verge of tears as she described how

much she owed the country, and how important the job was to

her. Commenting on Fox News, William Kristol, the

neoconservative pundit, concluded that Clinton had faked her

tears; while Brit Hume thought they were genuine. We'll

never know, of course. In the event, Clinton ended up

winning the primary, which also was distinguished by a failure

of pre-election polling to predict her win: most of the polls

had Obama ahead; it was not known whether respondents failed to

tell the truth about favoring Obama, or whether the episode led

to a last-minute surge in Clinton's support.

And here's another 'Muskie Moment", from

the New Hampshire presidential primary of January 2008.

Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton (D-NY), then in a neck-and-neck

battle with Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) was asked at an event in

a diner (New Hampshire is famous for these) how she kept up the

rigors of a campaign. Clinton's eyes welled up, her voice

broke, and she seemed on the verge of tears as she described how

much she owed the country, and how important the job was to

her. Commenting on Fox News, William Kristol, the

neoconservative pundit, concluded that Clinton had faked her

tears; while Brit Hume thought they were genuine. We'll

never know, of course. In the event, Clinton ended up

winning the primary, which also was distinguished by a failure

of pre-election polling to predict her win: most of the polls

had Obama ahead; it was not known whether respondents failed to

tell the truth about favoring Obama, or whether the episode led

to a last-minute surge in Clinton's support.

Here's

another example. This photograph by Spencer Platt is

titled "Beirut Residents continue to Flock to Southern

Neighborhoods" (as exhibited in "War/Photography: Images of

Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath" at the Brooklyn Museum,

2013-2014.. As explained by Ken Johnson, art critic

for the New York Times ("Poignant Images, with Posterity

the Ultimate Winner", 11/15/2013):

In a photograph shot by Spence Platt in Lebanon in 2006, the spectacle of five attractive, fashionably dressed young people in a glossy red convertible occupies the foreground. By surrealistic contrast, the immediate background is filled with the smoking wreckage of bombed buildings, where a few pedestrians pass by.... [T]he impression you get is of obnoxious rich kids out for a sensation-seeking drive. But the truth of Mr. Platt's picture, which won the 2006 World Press Photo of the Year award, was not what it seemed. In response to widespread criticism, the car's driver and passengers protested to news reporters that they were not disaster tourists but residents of the neighborhood returning to recover their belongings.

Perhaps

the most dramatic illustration

of the importance of context to social cognition is the famous

photograph of the "Vancouver

Riot Kiss", taken by Rich Lam during a riot that broke out

in Vancouver, British Columbia, in June 2011, after the Canucks

lost in the Stanley Cup hockey finals. Stripped of its

context, the photo appears to show a couple engaged in foreplay

(the inset is a similar still from From Here to Eternity,

a movie starring Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr). But the

original photograph shows that "The Kiss" actually took place

against a background of a street protest, with a police officer

wielding a truncheon in the foreground. But that only

makes the photo more ambiguous. What's going on here? Is

this a piece of performance art? An ironic act of social

protest? A Photoshopped hoax? Is he taking advantage

of her? It turned out that the couple involved, Scott

Jones and Alexandra Thomas, were caught up in the

mayhem. She was hurt in the melee, and he was trying

to comfort her (last I knew, they were still together, and had

hung the photo over their bed).

Other differences between social and

nonsocial cognition may be qualitative in nature.

Other differences between social and

nonsocial cognition may be qualitative in nature.

For example, the modularity of social cognition. Psychologists used to assume that thought followed the same rules, regardless of the topic -- and that, regardless of the topic, thinking was always performed by the same set of brain structures. That's where the idea of the "association cortex" comes from: there were certain areas of the brain devoted to sensory and motor functions, and then the rest was devoted to the formation of associations. Accordingly, it might be the case that people use the same mental apparatus, and underlying brain processes, to engage in social and nonsocial cognition. However, modern doctrine in neuroscience emphasizes modularity -- that different brain systems perform different mental functions. If so, it may well be that social-cognitive processes are handled by different mental modules, and

The idea of modularity goes back to the 19th-century phrenologists, who claimed to be able to diagnose mental capacities, and deficiencies, from the bumps on the surface of the skull. Interestingly, the "mental faculties" listed by the phrenologists included many functions that are expressly social in nature. Even if the neuroscientific doctrine of modularity is correct, we now know that the phrenologists got every detail wrong, in terms of their localization of mental faculties. Still, it might prove to be the case that the social and nonsocial aspects of cognition are mediated by distinctly different brain structures.

As it happens, a number of specifically "social" cognitive modules have been proposed. We'll talk about some of these at greater length later, in the lectures on Social-Cognitive Neuroscience, but here's just a sample.

Social cognition may or not involve different modules than nonsocial cognition, but there is one difference between the two that is distinct, and distinctly qualitative: social cognition blurs the distinction between subject and object. In nonsocial cognition, there is the subject -- the one who does the perceiving, or remembering, or thinking; and there is the object -- the thing that is perceived, remembered, or thought. But when we think of ourselves, we are simultaneously knower and the object of knowledge. Some social-cognition theorists claim that cognition of the self is different from cognition of other people, in that self-knowledge tends to follow different rules. Maybe. But even if the rules of self-cognition are the same as the rules of other-cognition, the fact that the same person is both subject and object is unique in the cognitive domain.

The fact that the self can be the object of social cognition adds a new dimension to the question of differences between social and nonsocial cognition. The basic problem can be stated thus:

Now we have to pose a further question:

Another clearly qualitative difference between social and nonsocial cognition has to do with the object of the enterprise. In social cognition, the stimulus situation is by definition composed of people, and people are sentient, intelligent beings, each with his or her own set of beliefs, feelings, and desires. In the social case, but not the nonsocial case, the object of cognition knows that it is the object of cognition; and that object has goals of his or her own, one of which may be to shape the perceiver's mental representations of him or her.

Put another way: In social cognition, we are trying to gain knowledge of the mental attributes of other people -- a process generally known as person perception or impression formation. But in person perception the "object of regard" is not passive, but rather conscious of being perceived, dynamically active, intelligently trying to shape the perceiver's percepts -- a process known as impression management (the term favored by the social psychologist E.E. Jones) or strategic self-presentation (the term favored by the sociologist E. Goffman).

Nowhere in nonsocial cognition is there any dynamic, dialectical interplay between impression formation on the part of an intelligent, conscious perceiver, and impression management on the part of an intelligent, conscious perceptual object.

Of course, the

observer, being a sentient, intelligent being him- or herself,

knows this, and so is constantly trying to "read between the

lines" with respect to the object. When we perceive other

people, we assume that they are trying to shape our perceptions,

and so we go to extra lengths to try to figure out what they are

really like.

Of course, the

observer, being a sentient, intelligent being him- or herself,

knows this, and so is constantly trying to "read between the

lines" with respect to the object. When we perceive other

people, we assume that they are trying to shape our perceptions,

and so we go to extra lengths to try to figure out what they are

really like.

The object knows this, of course, and therefore tries to manage the perceiver's impressions relatively subtly.

The perceiver knows this, too, and the object knows that the perceiver knows it.

The result

can be a kind of indefinite series, similar to an

infinite regress (except in this case it might be better termed

an infinite progress). We simply don't find this

problem in nonsocial cognition, for the simple reason that in

the nonsocial domain the object of perception is not an

intelligent, sentient being like the observer.

Iterated Knowing in EspionageMalcolm Gladwell, writing on "Operation Mincemeat" during World War II, in which the British tried to fool the Germans into thinking that the Allies were planing to invade Europe through Sardinia and Greece rather than Sicily and Italy:

For a philosophical examination of the problem of "iterated knowing", see J. Cargile, "A note on 'iterated knowings'",Analysis, 1970, 30, 151-155. |

The

dynamic interplay -- the dialectical relationship -- between

impression formation (on the part of the subject, the

perceiver) and impression management (on the part of

the object of perception) is vividly illustrated by the

"personals" ads published by many newspapers and magazines (my

own favorites come from the New York Review of Books),

in which two people -- the advertiser and the reader -- interact

with each other through the medium of newsprint.

Some personals ads are

relatively unambiguous.

Some personals ads are

relatively unambiguous.

Others, however, are a lot less

transparent, containing hidden meanings that must be

interpreted.

Others, however, are a lot less

transparent, containing hidden meanings that must be

interpreted.

Here are some more examples from the New York Review of Books. Think of them as exercises in person perception, not unlike the TAT card of the boy with the violin. What are these people like? How did they get that way? What do they want? Do you want to spend any time with them? What for?

|

|

|

|

For a collection of similar ads

from the London Review of Books, the NYRB's

sister publication, see the following books, both edited by

David Rose:

See also:

|

This page last modified 08/27/2015.