Park Effects in the MLB: How Teams are Built by their Stadiums

By Matthew Duston | April 11 , 2019

Ballparks are a central element for the MLB; iconic parks like Fenway and Wrigley have become instantly recognizable to people around the country through the decades. These ballparks are also uniquely important to baseball, as their different structures can have a massive impact on the game itself. While every basketball court, hockey rink, football field, and soccer pitch in professional sports is the same size, every ballpark in America is different and can play a different way. This may benefit hitters or pitchers, something that many teams take advantage of during team construction to make full use of the home park where they play half of their games.

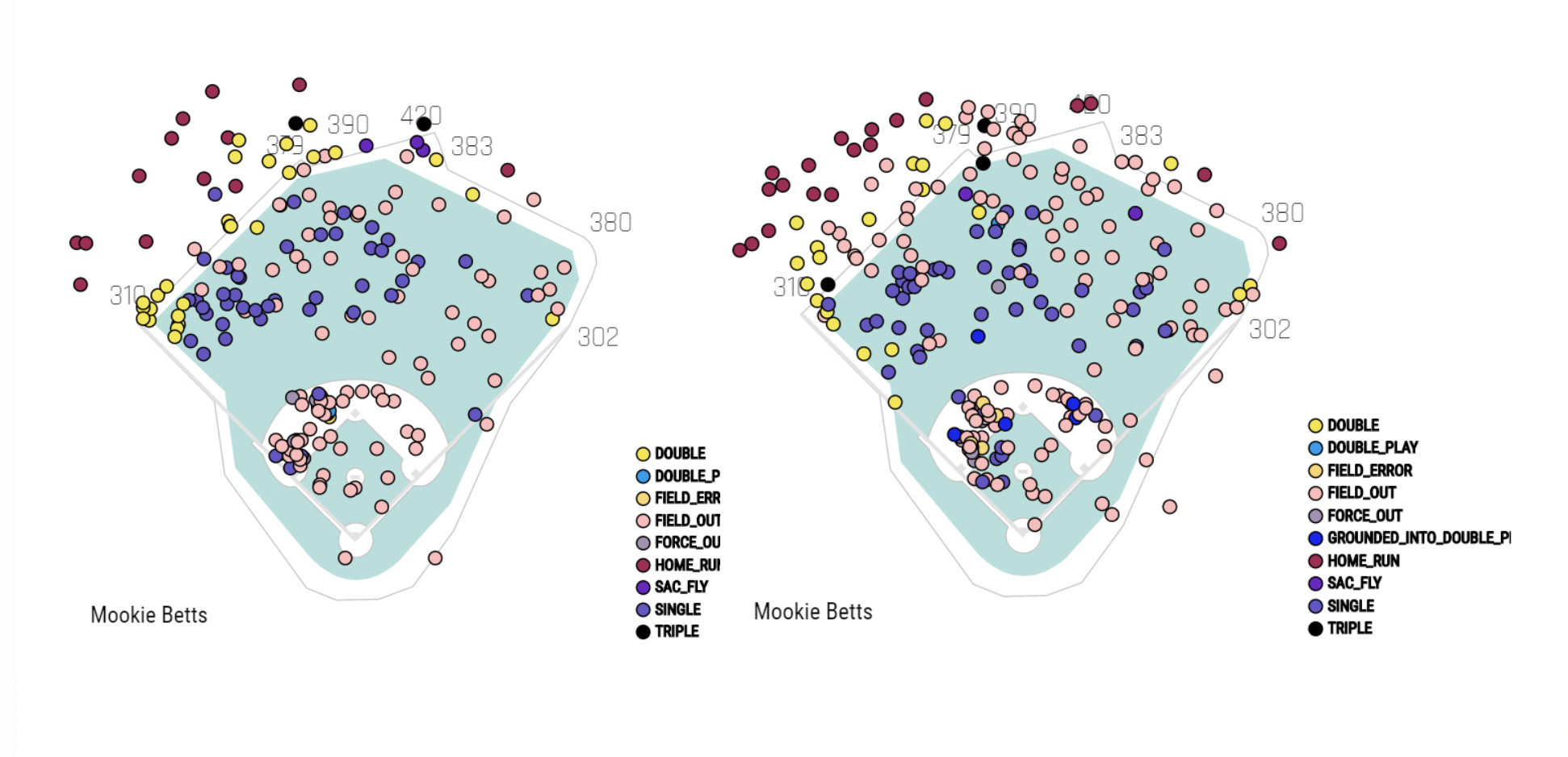

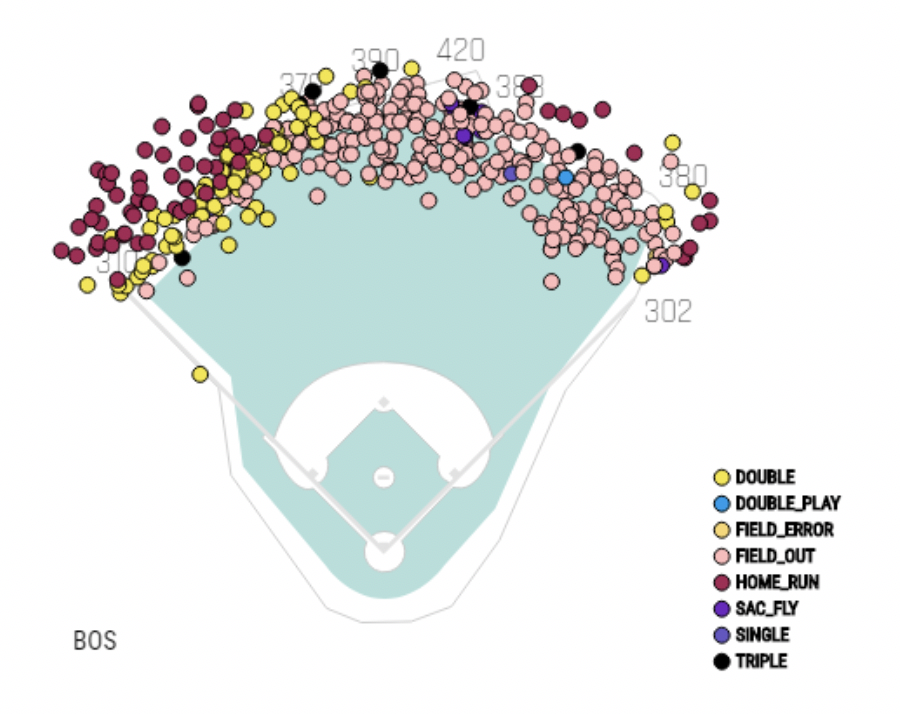

The effects of ballparks aren’t always obvious, but Fenway Park’s impact on the game can be seen every time a ball hits the 37-foot tall wall in left field. The “Green Monster” is an iconic part of one of the most famous ballparks in America, but it also gives the home team Boston Red Sox a significant advantage. Due to the wall’s height and proximity to home plate, not only are home runs easier to hit in that direction, but misses will bounce off the “Green Monster”, turning typical fly ball outs into doubles. This gives right-handed pull hitters, like Mookie Betts, a significant advantage while hitting at home. Take a look at all of Betts’ balls in play at home last year next to his balls in play away.

Many of the doubles Betts accrued at home would be outs in other ballparks, where many of the fly ball outs Betts makes while away would be doubles or home runs at Fenway. The Red Sox have taken advantage of this in their lineup, as 6 out of the 9 hitters starting at the world series were righties, with Benintendi and Devers as the two left-handed power bats for balance. By utilizing primarily righty lineups, the Red Sox can make the most of their park, and gain a significant advantage for half of their games.

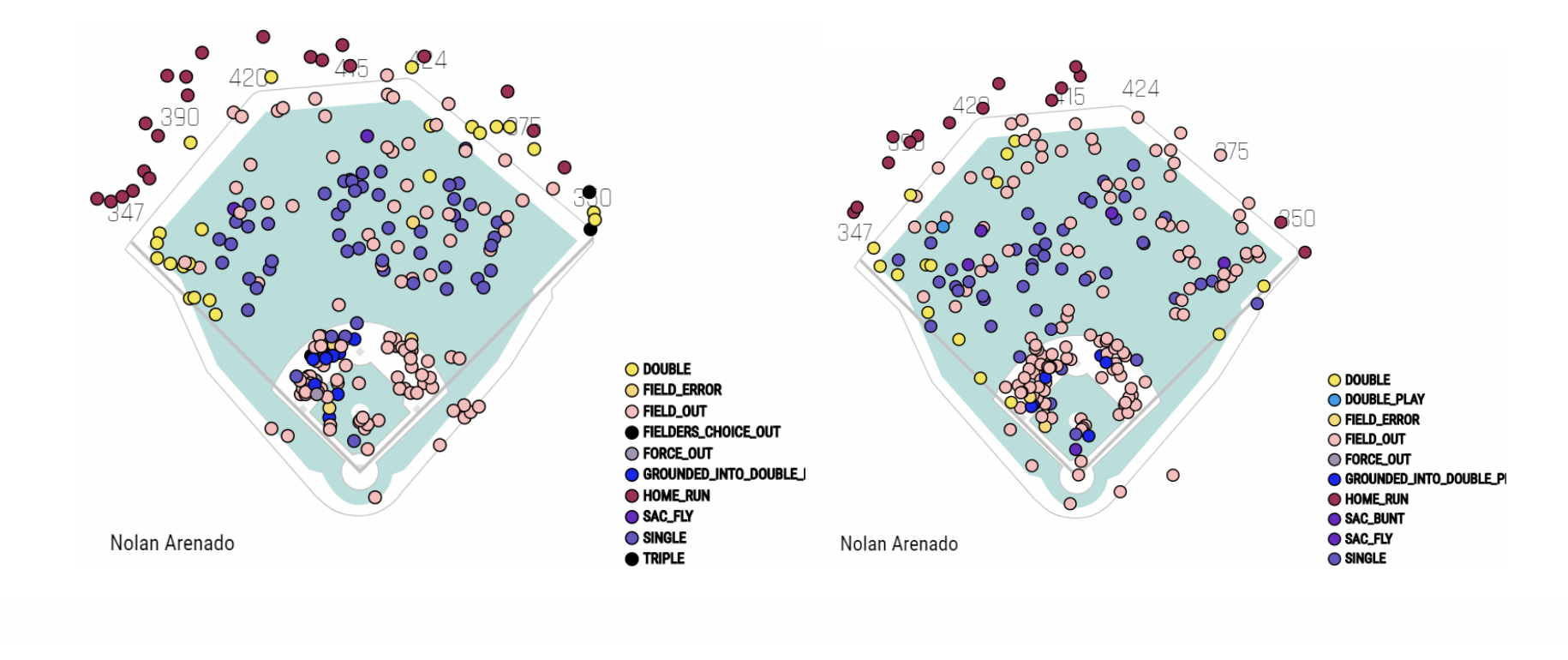

Ballpark construction isn’t the only cause for the large differences in MLB ballparks however, as the atmospheric conditions around the area can have a massive impact. Coors Field is the most well-known example, as the thin air at the 5,200 ft. elevation drastically increases the offense in the ballpark, something which benefits hitters significantly. Let’s take a look at the Colorado Rockies’ Nolan Arenado, and his balls in play at home and away.

Nolan Arenado hits balls a lot further at home compared to away, a factor that can be seen in his home and away splits: he has a 1.105 OPS at home compared to a .772 OPS away. To put the difference into perspective, a 1.105 OPS would have led the league last year over Mike Trout and Mookie Betts, while a .772 OPS would have been good for the 76th best in baseball, in between Mallex Smith and Teoscar Hernandez. That’s not a knock on Arenado, as the adjustment to Coors makes hitting away harder, and Arenado would be much better than a .772 OPS on another team, but the difference does help to emphasize the impact that a ballpark can have.

Fenway and Coors are two of the most obvious examples of ballpark bias, but how can we find some differences that can’t be seen looking at a spray chart? All hits can be roughly grouped together based on two statistics, launch angle, or the angle at which a hitter makes contact with the ball, and exit velocity, or the speed at which the ball comes off the bat. Balls in play with high launch angle are hit higher, balls with high exit velocity are hit harder, and balls with high exit velocity and launch angle are often home runs. With that in mind, let’s look at the average wOBA (weighted on-base average) for different exit velocities and launch angles across all MLB parks:

This is about what you’d expect, barreled balls hit 100+ mph and with a launch angle of 20 to 40 degrees are usually home runs and doubles, balls hit in the sweet spot of 60 to 70 mph exit velocity and 10 to 50 degree launch angles are bloop singles, and combinations with lower wOBAs are usually ground outs and fly outs. Now let’s compare the league average wOBA to similarly hit balls in a hitter-friendly park, Coors Field, and a pitcher-friendly one, Oracle Park:

Here, the green squares represent areas where wOBA is higher than the MLB average for a specific batted ball type, while the red squares represent areas where wOBA is lower. As you can see, balls hit 90+mph with LA of 20 to 50 degrees do significantly better in the thin atmosphere of Coors, and account for much of Coors’ hitter-friendly label. Oracle Park, meanwhile, is notorious for keeping high, hard-hit balls in the park due to the marine layer, and balls hit 100+ mph with LA between 20 and 40 do significantly worse than in other MLB parks. This data has a lot of noise, but charts like these can be useful in finding certain trends that are much more specific than the general ‘good for homers’ vs ‘bad for homers’ when looking at parks like Coors and Oracle. For example, let’s look at the chart for Fenway Park:

Balls hit 90 to 100 mph and with 30 to 40 LA do significantly better at Fenway than other MLB stadiums, and so it makes sense that the Red Sox can build a large advantage by stocking up on hitters who hit most of their balls at that trajectory. But why are these types of batted balls so effective at Fenway?

It turns out, this is where the “Green Monster” really comes into play, mainly benefitting balls hit in that sweet spot of 90 to 100 mph with LA between 30 and 40. Routine flyouts in most ballparks make it over the left field wall in Boston. The different characteristics of ballparks don’t just cause general effects of more or fewer homers, but instead, increase or decrease the effectiveness of batted balls based on their launch angle and exit velocity profile. By utilizing this information, teams can better select hitters that tend to hit at these trajectories, in order to build their teams to take advantage of their park’s unique characteristics.