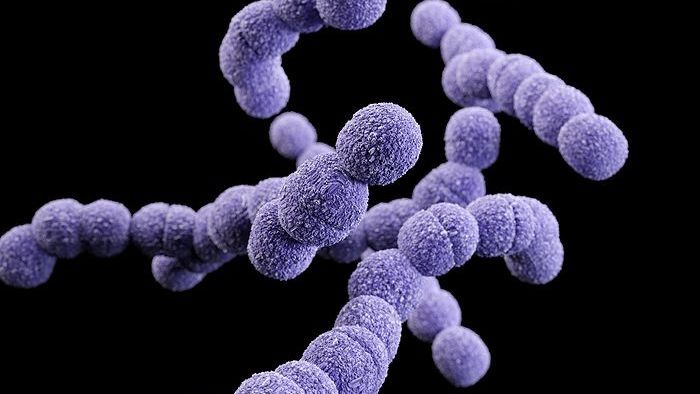

When I get sick, I rarely like to take medicine. Even if it means I will be sniffling and coughing for the next two weeks (this actually just happened), I would rather have my immune system fight off my flu than take unnecessary antibiotics. For more than 80 years, antibiotics have been the miracle drug for doctors to prescribe. Capable of killing bacteria without harming people, antibiotics have been able to cure a number of diseases that would have otherwise been deadly in the past. But now we prescribe antibiotics for every small ordeal—from ear infections to injecting it into healthy cows to fatten them up. Medical officers are now calling antibiotics a “ticking time bomb” because its overuse is building up a strong antibiotic resistance that could counter its medicinal purposes.

Since antibiotics kill bacteria without impunity, their fatal flaw is the bacteria immune to their wrath. These bacteria multiply and create a considerable population of antibiotic-resistant population that causes serious damage. In Europe alone, 25,000 people die every year from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Scientists are currently researching ways to understand this antibiotic resistance and discover new ways to fight the evolving bacteria. Most say we need to diversify the ways we treat bacterial infections and also reduce the amount of antibiotics we use.

Two pre-antibiotic medicines, serum therapy and bacteriophages, are making a comeback. Serum therapy is made up of antibodies—proteins that identify and attack bacteria—and bacteriophages—viruses that attack bacteria. The crucial difference with these medicines is that they are much more selective to which bacteria they kill, rather than the scorched-earth policy of antibiotics. To use serum therapy and bacteriophages, however, doctors must be extremely careful in figuring out which bacteria is causing the infection to treat it, because choosing wrong can lead to potentially deadly delays.

Antibiotics have made the doctor’s job easier, but they won’t work in the long run as they are already becoming less and less useful as resistant bacteria are evolving. By combining old ideas with new research, scientists have renewed interest in using phages and antibodies. For example, federal law has approved the use of antibacterial phages in our food supply and cloned antibodies for treatment of arthritis and cancer. In the future, more research can hopefully find better and more effective ways for us to wean off antibiotic use.

Article by Angie Zhang

Feature Image Source: BBC