The Mapo Bridge crosses the Han River in South Korea and connects two neighboring districts in the capital of Seoul. It is about 4,500 feet long, stretching over a short stint of blue amongst a busy skyline. Original construction was completed in 1970, and until 1984 the bridge was known as the Seoul Bridge, given its immediate location.

A hundred suicide attempts later, the bridge now has a new name: The Bridge of Death.

The South Korean government paired with Samsung to create a ‘Bridge of Life’ campaign in order to prevent more of these tragedies. Installations of inspirational messages, designed with motion sensors to ask questions like “How are you?” while people walked by were added to the bridge’s railings and sidewalks. The aim was to decrease suicide attempts by engaging with the attemptee through words instead of physical barriers.

Despite the efforts, one year after these installations, the suicide rate off the Mapo Bridge was six times higher.

Suicide in South Korea is unfortunately quite common. In fact, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or the OECD, South Korea comes in first amongst developed countries regarding suicide. Reasons for these suicides vary; many teenagers are facing pressure from school, others are dealing with bullying, adults are dealing with poverty, workplace demands are increasing while wages are stagnating, and more.

Image Source: The Drum

Amongst those groups, an unexpected demographic emerges: the elderly. Specifically, people over the age of 65. And one of the main causes for the spike in elderly suicide rates? The disruption of the traditional family unit, a problem that is becoming more common each year.

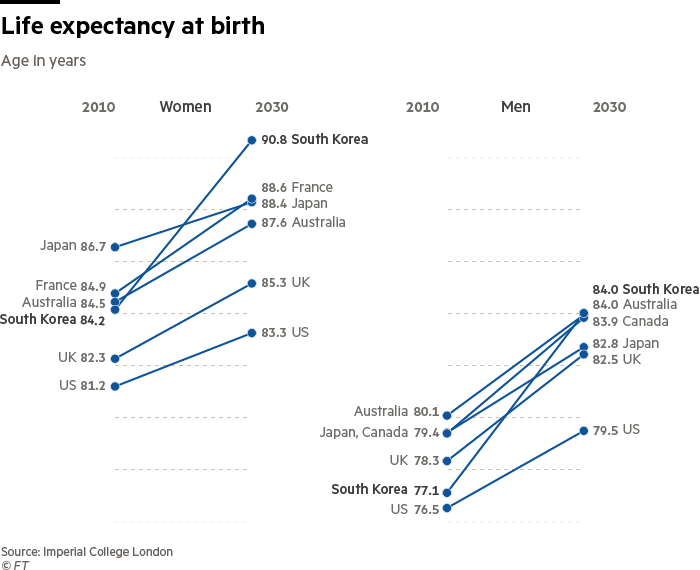

The population of the world’s elderly is growing rapidly. According to the U.S. Census Bureau in 2015, a projected 1.6 billion people will make up the elderly population by 2050. And that number continues to grow as time passes.

The causes of a rapidly aging population come from the advancements within the medical and public sectors over the last few years. A Stanford study revealed that people in developed countries can expect to live six years longer than their grandparents, with longevity being extended with each scientific breakthrough. While these advancements are revolutionary for the longevity of life, they also bring up new societal problems that no other generation has dealt with before.

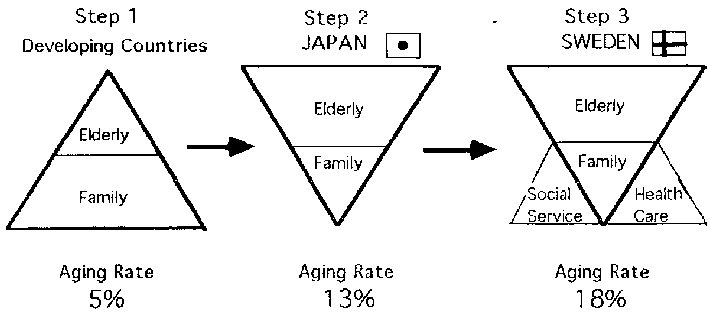

With an aging population that will only continue to grow, countries with large elderly populations are facing a globally unprecedented issue: how to properly care for a large influx of elderly people, while still moving towards the future.

Living longer is usually associated as being a hallmark of success, but current societal structures in many countries are not equipped to provide the social services needed. The lack of societal safety nets combined with changing cultural norms around the ideas of family are causing a bombardment of negative consequences to elderly people; consequences that are not easy to counteract.

Most will agree that the world is much more advanced than it was fifty years ago. Yet, with these advancements comes a new issue: figuring out how to care for this large wave of people living longer. If this issue isn’t tackled within the next few years, more cases like Korea will arise. More countries will have to deal with the effects of crippling depression, anxiety, and economic hardship on their own aging populations – that are inevitably growing.

What an aging population looks like: South Korea and Japan’s demographics

Between 1975 to 2015, South Korea’s median age rose from 19.6 to 41.2. In the city of Gangwon, a farming province, the median age is predicted to pass 60 by 2045. The fertility rate has dropped to one child per woman, or none at all. And with a rising life expectancy, young people in South Korea are getting harder to come by. By 2018, thousands of South Korean schools had been abandoned in the country because of the lack of their most valuable resource; students.

Image Source: Financial Times

Japan follows a similar story. Following years of population decline and historically low birth rates, Japan expects one in three of its citizens to be elderly by 2036. The birth rate in 2018 was the lowest it had been since 1899, and the population of 127 million people currently living in Japan is expected to drop to 100 million by 2049.

But why are these populations aging so rapidly, and why aren’t there younger people to replace them? Why are both of these developed countries not growing in population, but in fact declining?

One of the main reasons for the dropping fertility rates are the high demands regarding workplace culture and performance, making it difficult for Japanese and Korean workers to balance both their work life and personal life. In the 1990s, Japan introduced the world to the concept of “death from overwork”: a public health crisis of rising mortality rates from job related illnesses. And for South Korea, recent labor data from 2018 showed that South Koreans worked an average 240 more hours per year than Americans do – or a full additional month per year.

Hierarchical labor structures and high pressure from cultural norms play a role in both the Japanese and South Korean systems. After the Second World War, work was seen as a patriotic and national project to rebuild from the destruction of the war and stimulate both countries economies. But over time, this dedication intertwined with patriotism has become dangerous.

In South Korea, they have a word for the work culture that was created; gapjil. Gapjil describes the sense of entitlement that authority figures, or bosses, have over their employees, who are expected to always meet workplace demands. Japan’s equivalent is karoshi, or literally translating to “death by overwork”. And with these terms comes a sobering price: suicide.

According to 2018 South Korean government records, workplace pressure plays a role in more than 500 suicides a year, out of a national total of roughly 14,000. Japan has seen a similar rise in suicides and work related pressure, and saw the suicide rate reach its highest peak in more than 30 years – just last year.

With all of these troubling details, lower fertility rates, rapidly aging populations, and extreme workplace cultures, both Japan and South Korea are dealing with an unprecedented societal issue of an aging population. And the generation who helped shape today’s modern workers, who set in place this high pressure work mentality after the war and encouraged the development of gapjil and karoshi, are getting lost in all of it.

The changing family unit

Almost half of the elderly population in Korea live in poverty. Lee Sang-joon, a seventy-six year old South Korean pensioner, narrowly fits in his hostel room, tucked behind the stretching skyscrapers of Seoul’s skyline. He barely reaches five feet tall.

Image Source: Financial Times

Sixty-five year old Kim Cheung, a former trader, lives in a hovel in Dongjadong. None of her family or friends know of her living situation. She refuses to tell anyone.

It is in these elderly communities, hidden away from the bustling city life, where many of the elderly end up taking their own lives. As Lee Sang-joon explained, he does not want to bother his three children by asking for help.“They are too busy taking care of their own children,” he says. “I don’t want any support from them.”

Filial piety, caring for one’s parents’ mental and physical wellbeing when they reach old age, used to be a strong cultural value in Korea. But high unemployment amongst the youth, rapidly rising living costs, and drastic demographic changes regarding the older and younger populations have caused this concept to fade.

The Korean Women’s Development Institute conducted several studies in 2016, finding that more and more younger Koreans believe they are not responsible for their parents wellbeing as they age. Mirroring this thought, the elderly population over 65 expressed that they too do not believe their children should be solely in charge of their care. What was interesting from this study was a later statistic that was mentioned: both younger and older Koreans felt that the government and family unit, i.e. the children, should share the cost of elderly care – a number that has increased from 18.2 percent to nearly 47.3 percent in just over a decade.

South Korea’s lack of a social safety net for its poor provides a rude awakening to that desire. In 2019, Seoul reported that the gross national income per capita was $30,000, similar to that of Italy. But that wealth is not being distributed to the people who need it.

Kim Yang-ho, 78, lives on an allowance of $238 a month from the government. Nearly 1.5 million elderly Koreans qualify for this welfare subsidy, and 400,000 of those qualify for another subsidy called the “living wage”, starting at $440 a month. However, due to a loophole within the Korean welfare system, those 400,000 elders have their $238 allowance ultimately deducted from their $440 living wage, leaving with them with much less than they need, and what they were promised.

Image Source: The Borgen Project

It is after these deductions and failure of government services where the elderly find themselves living in hostels, picking up cans on the street to get by – all without disturbing their friends and families.

Kim Hotae, a 74 year old volunteer at a medical and legal group working in these areas, has seen these impacts with his own eyes.

“A lot of elderly people who leave here end up committing suicide because they are alone with no friends or neighbors,” he says. “Old people end up moving to this neighborhood because they have nobody else to rely on.”

A success story in Sweden

A different country on a neighboring continent is also facing an elderly age boom: Sweden. However, when compared to South Korea, Sweden’s governmental policies regarding the elderly are quite impressive.

For the most part, Swedish elderly care is largely funded by taxes. In fact, in 2014 the Swedish cost of elderly care was roughly 13 billion U.S. dollars, with only four percent of that spending budget financed by individual patient charges. There is also a diverse mix of private and public elderly care providers, allowing for elderly citizens to decide what type of care they’d like to utilize in order to best fit their personal lives.

More importantly, the types of services provided from both the public and private sectors are crucial to Sweden’s rank as one of the top countries in the world regarding elderly care. Municipalities in Sweden are responsible for elderly care, and provide funding for in home assistance to those who apply for it. Most regions offer regularly full cooked meals delivered to your door, and those who are unable to continue taking public transport immediately qualify for taxi and special adapted vehicle services – funded by the government.

Another large part of the Swedish system is the preventative measures put in place. Like Korea, Sweden projects to have a large elderly population in the years to come. By 2040, one in four Swedes will be over the age of 65. To prepare for this change, Sweden is directly engaging with their elderly population now, providing medical assistance as well as encouraging activities such as going on walks, painting, music events, and more. In most Swedish elderly homes, a resident will engage with at least one of those activities, if not more, in one day.

Image Source: WAO

Can the rest of the world figure it out?

Sweden may be a great example, but emulating its results worldwide will be tough. Not every country is as wealthy, homogeneous, or small as Sweden. And when comparing Swedish welfare practices to countries like South Korea and the United States, it almost seems impossible to transport their welfare state success to these already established, post-neoliberal social structures.

However, the key takeaways from the Swedish system are surprisingly simple: compassion and preparation. Viewing the elderly as an active group in society stimulates a whole new world of ideas to care for them. Addressing basic human needs beyond food and shelter, ones that encourage positive mental health through art or music or physical activity, seem to be the success stories for the elder Swedish population. Strong pushes from public and private funding also play a large role, and well thought out plans regarding transportation and meal services continue to make the task of living easier for elderly Swedes across the country.

Forgetting about an entire generation that helped create the future, for better or for worse, is a tragedy no country should endure. South Korea, Japan, Sweden, the United States, and more are facing this dilemma in real time, but there are solutions. Proper funding combined with empathy make for a strong social safety net, and more importantly, a stronger and happier older generation. At the end of the day, people should care about other people. Age should not hinder that.

Featured Image Source: Common Dreams